Effectiveness of Dignity Therapy in Patients with Advanced Cancer Receiving Palliative

Care: A Systematic Review

Article / Artículo

https://doi.org/10.33821/826

Date received: 14/10/2025

Date accepted: 19/11/2025

1. Introduction

The terminal phase of cancer represents a complex process, in which physical suffering

coexists with emotional distress, a high likelihood of loss of meaning, and an existential

crisis linked to the imminence of death. In this context, palliative care constitutes

a comprehensive approach (physical, psychological, social, and spiritual) aimed at

improving quality of life for patients and their families [1].

Among emerging interventions in this field, Dignity Therapy (DT) has gained recognition

as a brief, person-centered psychotherapeutic tool designed to alleviate existential

distress and promote a sense of worth, continuity of self, and legacy in patients

at the end of life [2,3]. Developed by Chochinov et al. in 2005, DT is structured around a semi-structured

interview whose responses are transcribed and edited to generate a document that can

be shared with whomever the patient chooses, functioning as a “life testimony” [4,5].

Numerous studies have described benefits of DT, such as reductions in anxiety and

depression, improvements in spiritual well-being, and enhanced perception of meaning

and personal control in the face of impending death [6-8]. However, its implementation across different clinical settings and specific populations,

such as patients with advanced cancer, has yielded variable results, thus making it

necessary to systematize the available evidence.

Recent studies conducted in different regions (Asia, Europe, and Latin America) reinforce

their usefulness in various cultures and clinical contexts by improving emotional

well-being and generating high levels of satisfaction [9,10]. Likewise, a culturally adapted version of DT for ambulatory oncology patients has

shown effectiveness in enhancing the sense of dignity and reducing distress in patients

with advanced-stage disease [11]. Among patients in a terminal condition, DT has been useful in reducing emotional

symptoms and, although no survival benefit was observed, its relevance has been consolidated

as an ethical and humanizing intervention in end-of-life care [12].

The increasing prevalence of patients with advanced cancer and the importance of comprehensively

addressing suffering in palliative care justify the need for a systematic review of

the effects of dignity therapy [13].

In this context, the aim of this systematic review was to evaluate the effectiveness

of Dignity Therapy in adult patients with advanced cancer receiving palliative care,

and to analyze its impact on perceived dignity, psychological and spiritual well-being,

and quality of life, compared with standard care.

2. Methodology

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 (Preferred

Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines [14]. The protocol was prospectively entered in the PROSPERO (International Prospective

Register of Systematic Reviews) database under registration number CRD420251109555.

2.1 Inclusion criteria

Randomized controlled trials and quasi-experimental studies evaluating Dignity Therapy

in adults (≥18 years) with advanced or terminal cancer receiving palliative care were

included. The intervention must correspond to the original Chochinov model, administered

in person or in a culturally adapted format. The comparison group was standard palliative

care. The primary outcome was perceived dignity, and secondary outcomes included anxiety,

depression, hope, spiritual well-being, and quality of life.

2.2 Exclusion criteria

Studies involving patients with severe cognitive impairment, combined psychosocial

interventions, pilot studies without complete results, review articles, short communications,

conference abstracts, and duplicate publications were excluded.

2.3 Search strategy

The literature search was completed on 20 July 2025. It was conducted without language

or date restrictions in five databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Scopus,

Web of Science). Search terms included MeSH (Medical Subject Headings) and free-text

terms related to dignity therapy, cancer, and palliative care. The main search string

was: (“Dignity Therapy” OR “dignity intervention”) AND (“Neoplasms” OR “Cancer”) AND

(“Palliative Care”). It was adapted for each database.

2.4 Study selection

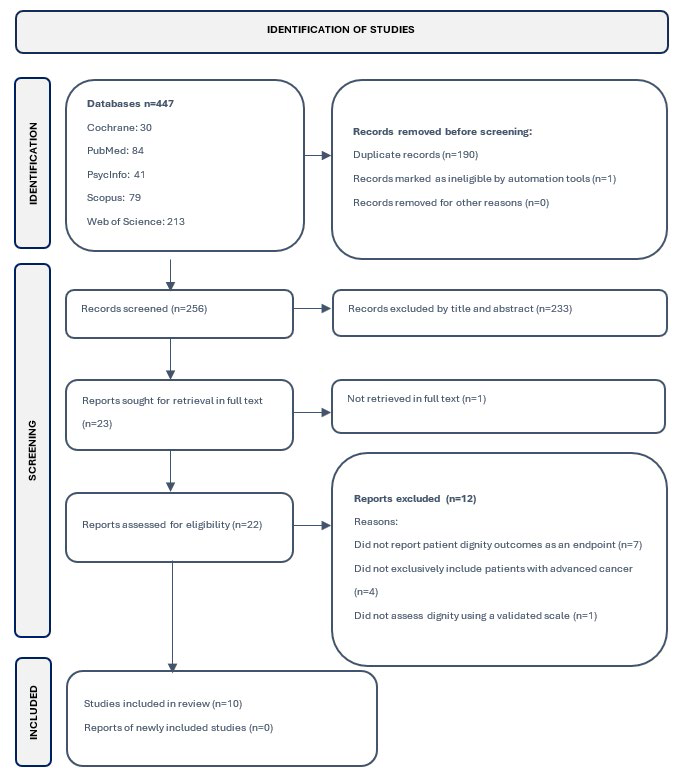

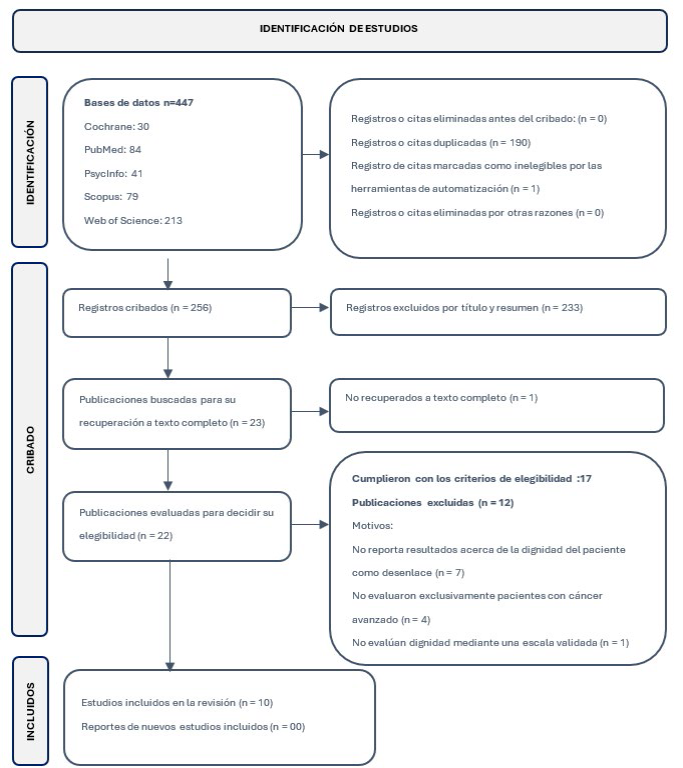

A total of 447 records were identified in electronic databases. After removing duplicates

(n = 190) and one ineligible record identified by automation tools, 256 titles and

abstracts were screened. Out of these, 233 were excluded for not meeting inclusion

criteria. Twenty-three full-text articles were assessed; 17 met the eligibility criteria

and were included in the qualitative synthesis [4,9-12,15-26]; ten provided adequate data for meta-analysis. The entire selection process is detailed

in Figure 1. Reference management was performed using Mendeley Reference Manager.

Figure 1.PRISMA

flow diagram of study selection for the systematic review.

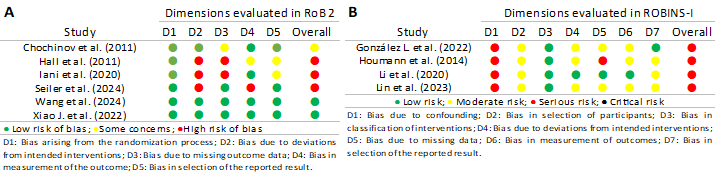

2.5 Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias was independently assessed by two reviewers using ROB 2 (Risk of Bias

2) for randomized controlled trials (RCTs) [27] and ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions) for non-randomized

studies [28]. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus or through a third reviewer (an independent

methodological and statistical consultant).

2.6 Data extraction

Information from each study was collected using a structured Excel template to ensure

uniformity and accuracy. General data (author, year, country, design, and sample size),

participant characteristics, cancer type, and care setting were extracted. Regarding

the intervention, the main features of Dignity Therapy (mode of delivery, duration,

professional in charge, and cultural adaptations) and the comparison group were recorded.

Primary and secondary outcomes (perceived dignity, psychological well-being, spirituality,

hope, and quality of life) were documented with the scales used and pre- and post-intervention

values. Data were verified by two independent reviewers, and disagreements were resolved

through consensus.

2.7 Data analysis

Quantitative analyses were performed using Jamovi (version 2.3.28). For continuous

outcomes (Patient Dignity Inventory scores and other scales), mean differences (MD)

with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated. For paired measures (pretest-posttest),

mean and standard deviation (SD) of the differences were used or derived from means

and SDs at each time point using standard formulas for repeated measures, assuming

a correlation coefficient based on the literature. Between-group comparisons (intervention

vs. control) used unstandardized mean differences. Random-effects models (DerSimonian

and Laird) were applied as the main estimator. Heterogeneity was assessed using I²,

Cochran’s Q test, and 95% prediction intervals, following the recommendations of Higgins

and Thompson [29]. Due to the small number of studies included in the comparative meta-analysis, publication

bias could not be reliably assessed.

3. Results

Ten studies published between 2011 and 2024 were included: five randomized controlled

trials and five pre-post quasi-experimental studies. Together, they comprised 904

adult patients with advanced or terminal cancer enrolled in palliative care programs

in North America (Canada, Mexico), Europe (Denmark, Italy, Switzerland), and Asia

(China, Taiwan). Sample sizes ranged from 24 to 326 participants, with a predominance

of women (53%) and an overall mean age of 63 years. Follow-up periods were short (7-30

days).

All studies implemented Dignity Therapy based on the original 2005 Chochinov model.

In general, the intervention consisted of an individual semi-structured interview

conducted by a trained professional (clinical psychologist, palliative care physician,

or nurse with specific training), usually in one or two sessions of 30-60 minutes,

transcribed into a legacy document. Most interventions were delivered in hospital

settings and focused on patients with advanced or terminal cancer, compared with standard

palliative care without a structured psychotherapeutic intervention. In some studies,

the protocol was linguistically or culturally adapted while preserving the essence

of the intervention.

In eight studies, the control group received only standard palliative care, consisting

of symptom control, non-structured psychosocial support, and clinical follow-up. In

two quasi-experimental studies, the intervention was evaluated using a pretest-posttest

design without a control group. No study used another structured psychotherapy as

a comparator, with the aim of isolating the specific effect of DT.

3.1 Risk of bias in the included studies

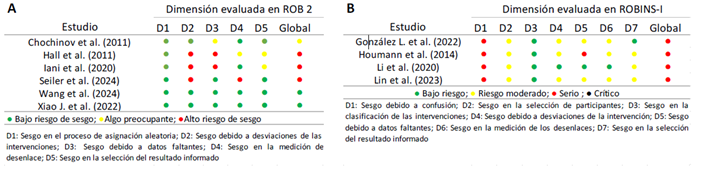

Methodological quality was variable. Among RCTs assessed with ROB 2 (Figure 2a), three showed high risk of bias due to lack of blinding and attrition, while two

presented an overall low risk of bias. Quasi-experimental studies, evaluated with

ROBINS-I, were classified as having a serious overall risk of bias, mainly due to

lack of a control group and non-random selection (Figure 2b).

Figure 2

Risk of bias in the included studies: RCTs assessed with ROB 2 (a) and quasi-experimental

studies assessed with ROBINS-I (b).

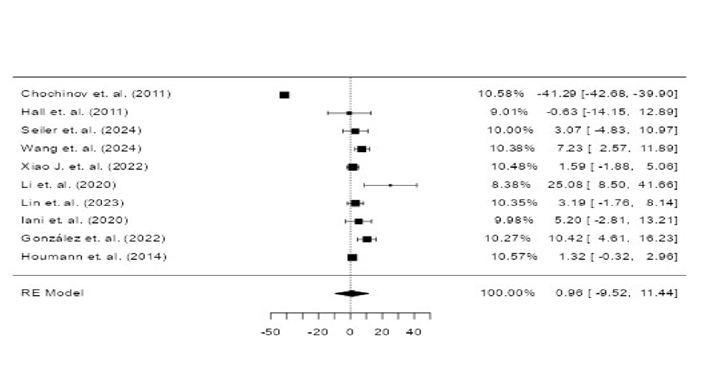

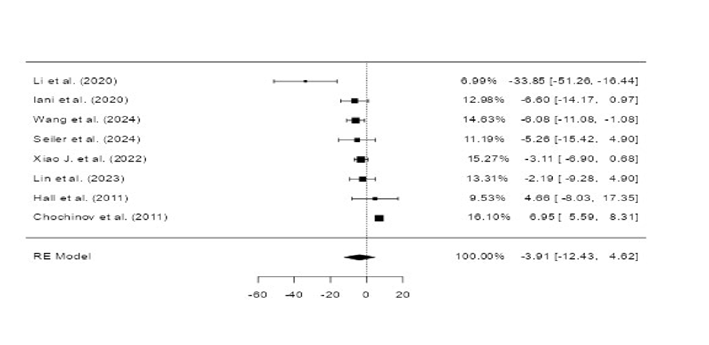

3.2 Effects on patient dignity

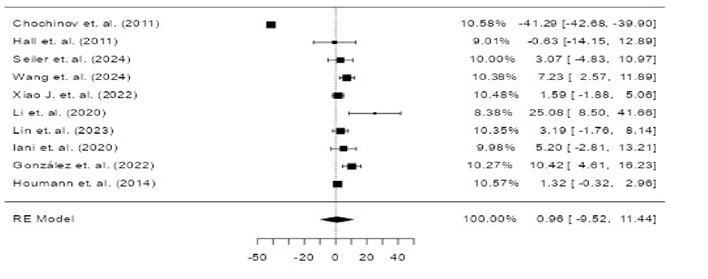

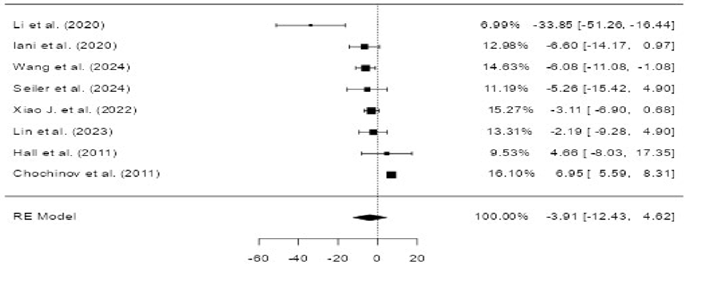

Meta-analysis of the ten included studies showed that Dignity Therapy did not produce

statistically significant differences in perceived dignity, either relative to baseline

or compared with standard palliative care.

In the pretest-posttest analysis, the mean difference was 0.96 (95% CI: -9.5 to 11.4),

whereas in the comparison with control groups the mean difference was -3.91 (95% CI:

-12.4 to 4.6) (Figures 3 and 4).

Both analyses showed high heterogeneity (I² > 90%), reflected in the wide dispersion

of confidence intervals in the forest plots.

Despite the absence of statistical significance, most studies reported favorable trends

in emotional well-being and sense of dignity. Therefore, it suggests a positive clinical

impact, although variable according to cultural context, methodological design, and

patient characteristics.

Figure 3

Forest plot of the pretest-posttest effect of Dignity Therapy. The large dispersion

of confidence intervals reflects considerable heterogeneity.

Figure 4

Forest plot of the effect of Dignity Therapy compared with control groups (8 studies).

The width of the confidence intervals reflects the observed heterogeneity.

3.3 Effects of Dignity Therapy on other outcomes

Beyond its effect on patient dignity, evidence was found for other outcomes such as

reductions in anxiety and depression, improvements in spiritual well-being, hope,

quality of life, preparat0069on for death, reduction of existential suffering, and

fatigue. A synthesis of the evidence for these outcomes is presented below.

3.3.1 Anxiety and depression

Several studies used the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) to measure anxiety

and depression. In the trial by Chochinov et al. (2011), no statistically significant

differences were found between patients who received DT and those in the control group,

although there was a trend toward lower symptomatology in the intervention group [26]. Similar findings were reported by Houmann et al. (2014) and Hall et al. (2011);

in these, DT did not yield significant changes compared with control groups but did

provide qualitative benefits reported by participants [23,24].

By contrast, studies by Li et al. (2020) and Iani et al. (2020) showed significant

reductions in both anxiety and depression following DT [20,25]. More recently, Seiler et al. (2024) and Wang et al. (2024) also confirmed statistically

significant improvements in these outcomes, thus suggesting that the impact of DT

may depend on cultural factors and the context in which it is implemented [17,18].

3.3.2 Spiritual well-being

The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp)

was used in studies by Chochinov et al. (2011) and Houmann et al. (2014). Although

no significant differences were found compared with controls, both studies reported

that patients perceived a greater sense of purpose and inner peace after DT. This

is a relevant qualitative contribution [23,26].

3.3.3 Hope, preparation for death, and existential suffering

The Herth Hope Index (HHI) was evaluated by Hall et al. (2011), who found significant

increases in hope levels in the DT group compared with controls [24]. Chochinov et al. (2011) assessed preparation for death and reported that patients

who received DT felt better prepared, although quantitative comparisons did not reach

statistical significance [26]. Similarly, Houmann et al. (2014) documented improvements in perceived existential

control and adaptation to the end-of-life process [23]. Together, these findings reinforce the qualitative dimension of DT as supportive

therapy in the transition toward death.

3.3.4 Quality of life

Quality of life was assessed in several studies using different instruments, including

the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire

- Core 15 Palliative (EORTC-QLQ-C15-PAL). Houmann et al. (2014) and Li et al. (2020)

reported improvements in specific domains (emotional well-being and social functioning),

although findings were not consistent across all dimensions of the questionnaire [20,23]. Wang et al. (2024) reported significant global improvements when DT was combined

with family-focused interventions [17].

3.3.5 Fatigue and physical suffering

Xiao et al. (2024) included measures of fatigue and physical symptoms associated with

advanced cancer and observed clinically relevant reductions after the intervention

[19]. Although results were not consistent across all domains, these findings suggest

that DT may indirectly contribute to the reduction of physical suffering through psychological

relief.

4. Discussion

Findings reported in this systematic review indicate that Dignity Therapy is a brief,

patient-centered intervention designed to address existential and psychological suffering

in the context of advanced disease. Although the review did not demonstrate a statistically

significant effect on the primary outcome of perceived dignity, relevant benefits

were observed in reducing anxiety and depression and increasing hope and spiritual

well-being. These results suggest that DT may have an important clinical impact on

emotional and existential domains, even when quantitative findings are heterogeneous.

The high heterogeneity observed (I² > 90%) reflects methodological differences between

studies, including diverse designs (RCTs vs. quasi-experimental studies), small sample

sizes, and the use of different scales to measure dignity, spirituality, and quality

of life. Such limitations are common in reviews of psycho-spiritual interventions,

where the subjectivity of outcomes and cultural variation hinder comparability [2,3].

In randomized controlled trials assessed with ROB 2, risk of bias was identified in

domains such as blinding and loss to follow-up [18,24,25]. Nonetheless, studies with greater methodological rigor, such as those by Wang et

al. [17] and Xiao et al. [19], demonstrated significant reductions in anxiety and depression, underscoring the

potential effectiveness of DT when more controlled designs are implemented.

Quasi-experimental studies assessed with ROBINS-I showed a serious risk of bias due

to participant selection and lack of control for confounding [10,23]. Even so, they provide valuable information regarding the feasibility and acceptability

of DT in real-world clinical practice. Experiences in Mexico and China are particularly

illustrative of the relevance of cultural factors in perceived effectiveness, where

family and community play a central role in the end-of-life experience.

Another notable aspect is the consistency of qualitative findings reporting significant

benefits: a greater sense of being accompanied, reaffirmation of identity, resolution

of unfinished business, and creation of a legacy for family members [4,8]. Although difficult to quantify, these dimensions reflect the ethical and humanizing

value of DT, aligned with Chochinov’s dignity-conserving care framework [30], which considers identity, autonomy, and continuity of self as pillars of compassionate

end-of-life care.

European evidence, particularly the work of Julião et al. [12] in Portugal, shows that DT does not impact survival but does reduce psychological

distress and improve emotional well-being. This confirms that the main contribution

of DT lies in the existential domain, reinforcing patients’ dignity and autonomy at

the end of life.

Finally, it should be emphasized that DT does not replace conventional medical or

psychosocial care but rather complements it, enhancing comprehensive management. Integrating

DT into palliative care protocols would strengthen holistic care, especially in Latin

American contexts where family, spiritual, and cultural values are central to the

experience of illness and death [31].

5. Conclusions

Dignity Therapy emerges as a feasible, safe, and well-accepted intervention for patients

with advanced cancer, with consistent benefits in emotional and existential domains.

Its effects are expressed mainly through reductions in anxiety and depression, increased

hope, and strengthened spiritual well-being-components that influence quality of life

and coping with end-of-life processes.

Although quantitative results for perceived dignity did not reach statistical significance,

qualitative evidence and the consensus of the reviewed studies indicate that DT provides

clinical and human value, reaffirming patient identity and contributing to more compassionate,

person-centered care.

Methodological heterogeneity, small sample sizes, and identified risks of bias limit

the generalizability of findings; however, the convergence of qualitative and quantitative

results supports the usefulness of DT as an ethical and humanizing intervention in

palliative care. Taken together, DT improves the quality of the dying process by facilitating

biographical closure, expression of meaning, and preservation of the patient’s personal

legacy.

6. Recommendations

It is recommended to integrate Dignity Therapy as a complementary component of palliative

care programs, with protocols adapted to the cultural, spiritual, and family idiosyncrasies

of each population. Training health professionals in DT within interdisciplinary teams

would help strengthen comprehensive, person-centered care models.

In addition, multicenter studies with greater methodological rigor-particularly randomized

controlled trials with larger samples and longitudinal follow-up-are needed to confirm

the observed benefits and explore DT’s mechanisms of action across different clinical

and cultural contexts.

The use of mixed methods (quantitative and qualitative) should be promoted to capture

the full range of intervention effects, given that many of DT’s benefits transcend

what can be measured quantitatively. Finally, the generation of evidence in Latin

America should be encouraged, as DT has shown high acceptability and cultural relevance

in this region, where its integration may foster more humane, compassionate, and spiritually

sensitive end-of-life care.

1. Introducción

La fase terminal en el paciente oncológico representa un proceso complejo, en el que

se evidencia sufrimiento físico, afectación emocional con alta probabilidad de pérdida

de sentido y crisis existencial relacionada con la proximidad de la finitud. En este

contexto, los cuidados paliativos se constituyen como un enfoque integral (físico,

psicológico, social y espiritual) destinado a mejorar la calidad de vida del paciente

y su entorno [1].

Entre las intervenciones emergentes en este campo, la terapia de la dignidad (TD)

ha ganado reconocimiento como una herramienta psicoterapéutica breve, centrada en

la persona, diseñada para aliviar el sufrimiento existencial y promover un sentido

de valor, continuidad del yo y legado para el paciente al final de la vida [2,3]. Desarrollada por Chochinov et al. en 2005 [4,5], la TD se estructura en torno a una entrevista semiestructurada cuyas respuestas

se transcriben y editan para generar un documento que puede ser compartido con quien

el paciente lo desee, así que funciona como un “testimonio de vida”.

Numerosos estudios han señalado beneficios de la TD, como la disminución de la ansiedad

y la depresión, mejora del bienestar espiritual la percepción del sentido y el control

personal ante la proximidad de la muerte [6-8]. Sin embargo, su implementación en distintos entornos clínicos y poblaciones específicas,

como pacientes con cáncer avanzado, ha generado variabilidad en los resultados, por

lo que es necesario sistematizar la evidencia disponible.

Estudios recientes realizados en distintas regiones (Asia, Europa y América Latina)

refuerzan su utilidad en diferentes culturas y contextos clínicos: ha mejorado el

bienestar emocional y se han generado altos niveles de satisfacción [9,10]. Asimismo, una versión culturalmente adaptada de la TD para pacientes oncológicos

en tratamiento ambulatorio mostró ser eficaz en mejorar el sentido de dignidad y reducir

la angustia en pacientes en etapa avanzada [11]; en pacientes en situación de terminalidad, la TD fue útil para para reducir síntomas

emocionales, y aunque no se evidenció un aumento en la supervivencia, se consolidó

su relevancia como intervención ética y humanizadora en el acompañamiento del final

de vida [12].

La creciente prevalencia de pacientes con cáncer en fases avanzadas y la importancia

de abordar de forma integral el sufrimiento en cuidados paliativos justifican la necesidad

de revisar sistemáticamente los efectos de la terapia de la dignidad [13].

En este contexto, la presente revisión sistemática tuvo como objetivo evaluar la efectividad

de la TD en pacientes adultos con cáncer avanzado que reciben cuidados paliativos,

analizando su impacto en la dignidad percibida, el bienestar psicológico, espiritual

y la calidad de vida en comparación con los cuidados estándar.

2. Metodología

Esta revisión sistemática se llevó a cabo conforme a las directrices de la declaración

PRISMA 2020 (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [14]. El protocolo fue registrado de forma prospectiva en la base de datos PROSPERO (International

Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) bajo el número de registro [CRD420251109555].

2.1 Criterios de inclusión

Se incluyeron ensayos clínicos aleatorizados y estudios cuasiexperimentales que evaluaron

la TD en adultos (≥ 18 años) con cáncer avanzado o terminal en cuidados paliativos.

La intervención debía corresponder al modelo original de Chochinov, aplicada de forma

presencial o culturalmente adaptada. El grupo comparador fue el expuesto a la atención

paliativa estándar. El desenlace principal fue la dignidad percibida, y los secundarios

incluyeron ansiedad, depresión, esperanza, bienestar espiritual y calidad de vida.

2.2 Criterios de exclusión

Se excluyeron estudios en pacientes con deterioro cognitivo severo, intervenciones

psicosociales combinadas, estudios piloto sin resultados completos, artículos de revisión,

comunicaciones breves, resúmenes de congresos y duplicados.

2.3 Estrategia de búsqueda

La búsqueda se finalizó el 20 de julio del 2025. Esta se realizó sin restricciones

de idioma ni fecha en cinco bases de datos (PubMed, Cochrane Library, PsycINFO, Scopus,

Web of Science). Los términos de búsqueda incluyeron combinaciones con términos MeSH

(Medical Subject Headings) relacionados con la terapia de la dignidad, cáncer y cuidados

paliativos. La estrategia de búsqueda fue la siguiente: ("Dignity Therapy" OR "dignity

intervention") AND ("Neoplasms" OR "Cancer") AND ("Palliative Care"). Esta estrategia

fue adaptada a las bases de datos correspondientes.

2.4 Selección de estudios

Se identificaron 447 registros en las bases de datos electrónicas. Tras eliminar duplicados

(n = 190) y un registro inelegible por automatización, se cribaron 256 títulos y resúmenes.

Se excluyeron 233 por no cumplir con los criterios de inclusión. Se evaluaron 23 estudios

a texto completo, de los cuales 17 cumplieron con los criterios de elegibilidad y

fueron incluidos en la revisión cualitativa [4,9-12,15-26]; diez de ellos aportaron datos adecuados para el metaanálisis. El proceso completo

de selección se detalla en la Figura 1. La gestión de referencias se llevó a cabo utilizando Mendeley Reference Manager.

Figura 1. Diagrama

de flujo (PRISMA) de selección de los estudios incluidos en la revisión.

2.5 Evaluación del riesgo de sesgo

El riesgo de sesgo fue evaluado de forma independiente por dos revisores utilizando

ROB 2 (Risk of Bias 2) [27] para los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados (ECA) y ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias in Non-randomized

Studies of Interventions) [28] para los estudios no aleatorizados. Las discrepancias se resolvieron por consenso

o mediante un tercer revisor (consultor metodológico y estadístico independiente).

2.6 Extracción de datos

La información de cada estudio se recopiló mediante una plantilla de Excel estructurada

que garantizó uniformidad y precisión. Se extrajeron datos generales (autor, año,

país, diseño y tamaño muestral), características de los participantes, tipo de cáncer

y contexto asistencial. En cuanto a la intervención, se registraron las principales

características de la TD (modalidad, duración, profesional responsable y adaptaciones

culturales) y del grupo comparador. Los desenlaces principales y secundarios (dignidad

percibida, bienestar psicológico, espiritualidad, esperanza y calidad de vida) se

documentaron con las escalas empleadas y los valores pre y posintervención. La información

fue verificada por dos revisores independientes y las discrepancias se resolvieron

por consenso.

2.7 Análisis de los datos

El análisis cuantitativo se realizó utilizando Jamovi (versión 2.3.28). Para los desenlaces

continuos (puntuaciones del Patient Dignity Inventory y otras escalas), se calcularon

diferencias de medias (DM) con sus intervalos de confianza (IC) del 95 %. En medidas

pareadas (pretest-postest) se empleó la media y desviación estándar (DE) de las diferencias,

o se calcularon a partir de las medias y DE de cada momento aplicando la fórmula para

medidas repetidas, asumiendo un coeficiente de correlación basado en la literatura.

Las comparaciones entre grupos (intervención vs. control) utilizaron DM no estandarizada.

Se aplicaron modelos de efectos aleatorios (DerSimonian y Laird) como estimador principal.

La heterogeneidad se evaluó mediante I², prueba Q de Cochran e intervalo de predicción

al 95 % de acuerdo con las recomendaciones de Higgins y Thompson [29]. No fue posible evaluar de manera confiable el sesgo de publicación debido al número

reducido de estudios incluidos en el metaanálisis de comparación.

3. Resultados

Se incluyeron diez estudios publicados entre 2011 y 2024, cinco ensayos clínicos aleatorizados

y cinco estudios cuasiexperimentales pre-post. En conjunto, abarcaron 904 pacientes

adultos con cáncer avanzado o terminal atendidos en programas de cuidados paliativos

en América del Norte (Canadá, México), Europa (Dinamarca, Italia, Suiza) y Asia (China,

Taiwán). Las muestras variaron entre 24 y 326 participantes, con predominio de mujeres

(53 %) y edad media global de 63 años. Los seguimientos fueron breves (7-30 días).

Todos los estudios aplicaron la TD, con base en el modelo de Chochinov de 2005; la

intervención consistió, de forma general, en una entrevista semiestructurada individual,

guiada por un profesional entrenado (psicólogo clínico, médico especialista en cuidados

paliativos o enfermero con formación específica) generalmente en una o dos sesiones

individuales de 30-60 minutos, transcritas como documento de legado. La mayoría se

desarrolló en el ámbito hospitalario, se centraron en pacientes con cáncer avanzado

o terminal, comparando con cuidados paliativos estándar sin intervención psicoterapéutica

estructurada. En algunos casos se adaptó lingüística o culturalmente, manteniendo

la esencia del protocolo.

En ocho estudios, el grupo control recibió únicamente la atención de cuidados paliativos,

consistente en control de síntomas, apoyo psicosocial no estructurado y seguimiento

clínico. En dos estudios cuasiexperimentales, la intervención se evaluó con un diseño

pretest-postest sin grupo control. Ningún estudio incluyó otra psicoterapia estructurada

como comparador, con el objetivo de aislar el efecto específico de la TD.

3.1 Riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos

La calidad metodológica fue variable. En los ECA evaluados mediante ROB 2 (Figura 2a), tres mostraron riesgo alto por ausencia de cegamiento y pérdidas de seguimiento,

mientras que dos presentaron bajo riesgo global. En los estudios cuasiexperimentales,

evaluados con ROBINS-I fueron clasificados con riesgo global serio principalmente

por falta de grupo control y selección no aleatoria (Figura 2.b).

Figura 2

Riesgo de sesgo de los estudios incluidos: ECA evaluados con ROB 2 (a) y estudios

cuasiexperimentales con ROBINS-I (b).

3.2 Efectos sobre la dignidad del paciente

El metaanálisis de los diez estudios incluidos mostró que la TD no produjo diferencias

estadísticamente significativas en la dignidad percibida respecto al valor basal ni

frente a los cuidados paliativos estándar.

En el análisis pretest-postest, la diferencia media fue de 0,96 (IC 95 %: -9,5 a 11,4),

mientras que en la comparación con el grupo control fue de -3,91 (IC 95 %: -12,4 a

4,6) (Figuras 3 y 4).

Ambos análisis evidenciaron alta heterogeneidad (I² > 90 %), reflejada en la amplia

dispersión de los intervalos de confianza de los forest plots.

Pese a la ausencia de significancia estadística, la mayoría de los estudios reportó

tendencias favorables en bienestar emocional y sentido de dignidad, lo que sugiere

un impacto clínico positivo, aunque variable según el contexto cultural, diseño metodológico

y características de los pacientes.

Figura 3

Forest plot del efecto pretest-postest de la TD. Se observa gran dispersión de los intervalos

de confianza y heterogeneidad considerable.

Figura 4

Forest plot del efecto de la TD frente al grupo control (ocho estudios). La amplitud de los intervalos

de confianza refleja la heterogeneidad observada.

3.3 Efectos de la terapia de la dignidad sobre otros aspectos

Además de evaluar el efecto sobre la dignidad del paciente, se encontró evidencia

sobre otros desenlaces como disminución de la ansiedad y depresión, mejora de la percepción

del bienestar espiritual, esperanza, calidad de vida, preparación para la muerte,

reducción del sufrimiento existencial y fatiga. A continuación, se presenta una síntesis

de la evidencia relacionada con estos desenlaces.

3.3.1 Ansiedad y depresión

Varios estudios emplearon la Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) como instrumento

para medir ansiedad y depresión. En el ensayo de Chochinov et al. del 2011 [26], no se encontraron diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los pacientes

que recibieron TD en comparación con el grupo control, aunque sí se observaron tendencias

a menor sintomatología en el grupo de intervención. Resultados similares se reportaron

en Houmann et al. (2014) y Hall et al. (2011) [23,24], estudios en los que la TD no mostró cambios significativos en comparación con los

grupos control, pero aportó beneficios cualitativos señalados por los participantes.

Por otra parte, los estudios de Li et al. (2020) e Iani et al. (2020) [20,25] evidenciaron reducciones significativas tanto en ansiedad como en depresión tras

la intervención con la TD. Más recientemente, Seiler et al. (2024) y Wang et al. (2024)

[17,18] también confirmaron mejoras estadísticamente significativas en estos desenlaces,

y esto sugiere que el impacto de la TD puede depender de factores culturales y del

contexto de aplicación.

3.3.2 Bienestar espiritual

El Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy - Spiritual Well-Being (FACIT-Sp)

fue utilizado en Houmann et al. (2014) y en Chochinov et al. (2011) [23,26]. Aunque no se alcanzaron diferencias significativas frente al control, ambos estudios

señalaron que los pacientes percibieron un mayor sentido de propósito y paz interior

tras la TD, lo cual constituye un aporte cualitativo relevante.

3.3.3 Esperanza, preparación para la muerte y sufrimiento existencial

La Herth Hope Index (HHI) fue evaluada en Hall et al. (2011) [24], estos autores observaron incrementos significativos en los niveles de esperanza

en el grupo tratado con la TD frente al control. Por otro lado, Chochinov et al. (2011)

[26] evaluaron la preparación para la muerte y reportaron que los pacientes que recibieron

la TD se sintieron mejor preparados, aunque sin alcanzar significancia estadística

en las comparaciones cuantitativas. En línea con ello, Houmann et al. (2014) [23] documentaron mejoras en la percepción de control existencial y en la adaptación

al proceso de final de vida. Estos resultados refuerzan la dimensión cualitativa de

la TD como apoyo en la transición hacia la muerte.

3.3.4 Calidad de vida

La calidad de vida fue medida en múltiples estudios mediante diferentes instrumentos,

incluida la European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of

Life Questionnaire (EORTC-QLQ-C15-PAL). En Li et al. (2020) y Houmann et al. (2014)

[20,23], se reportaron mejoras en algunos dominios específicos (bienestar emocional y funcionalidad

social), aunque no consistentes en todas las dimensiones del cuestionario. Wang et

al. (2024) [17] identificaron mejoras globales significativas cuando la TD se combinó con intervenciones

familiares.

3.3.5 Fatiga y sufrimiento físico

El estudio de Xiao et al. (2024) [19] incluyó medidas de fatiga y síntomas físicos asociados al cáncer avanzado; además,

se observaron disminuciones clínicamente relevantes tras la intervención. Aunque los

resultados no fueron consistentes en todos los dominios, estos sugieren que la TD

podría contribuir indirectamente a la reducción de sufrimiento físico a través del

alivio psicológico.

4. Discusión

Los hallazgos de esta revisión sistemática muestran que la TD es una intervención

breve en comparación con otras terapias psicológicas y centrada en el paciente, diseñada

para abordar el sufrimiento existencial y psicológico en el contexto de la enfermedad

avanzada. Si bien la revisión sistemática no demostró un efecto estadísticamente significativo

en el desenlace primario de dignidad percibida, sí se evidenciaron beneficios relevantes

en la reducción de ansiedad y depresión, en el incremento de esperanza y en el bienestar

espiritual. Estos hallazgos sugieren que la TD puede tener un impacto clínico importante

en dominios emocionales y existenciales, aun cuando los resultados cuantitativos sean

heterogéneos.

La alta heterogeneidad encontrada (I² > 90 %) refleja las diferencias metodológicas

entre los estudios, incluida diversidad en los diseños (ECA vs. cuasiexperimentales),

tamaños muestrales reducidos y uso de escalas distintas para medir dignidad, espiritualidad

y calidad de vida. Estas limitaciones son comunes en revisiones sobre intervenciones

psicoespirituales, en las que la subjetividad de los resultados y las variaciones

culturales afectan la comparabilidad [2,3].

En los ECA evaluados con la herramienta ROB 2, se identificó riesgo de sesgo en dominios

como cegamiento y pérdidas de seguimiento [18,24,25]. A pesar de ello, estudios con

mayor rigor metodológico, como los de Wang et al. [17] y Xiao et al. [19] demostraron reducciones significativas en ansiedad y depresión, lo que resalta la

eficacia potencial de la TD cuando se aplican diseños más controlados.

Los estudios cuasiexperimentales evaluados con ROBINS-I presentaron riesgo serio de

sesgo por selección de participantes y falta de control de confusión [10,23]. No obstante, aportan información valiosa en cuanto a la factibilidad y aceptabilidad

de la TD en la práctica clínica real. En particular, las experiencias en México y

China muestran la relevancia de factores culturales en la efectividad percibida, en

la que la familia y la comunidad juegan un papel central en la experiencia de fin

de vida.

Otro aspecto para destacar es que los resultados cualitativos son consistentes en

reportar beneficios significativos: mayor sensación de acompañamiento, reafirmación

de la identidad, cierre de asuntos pendientes y generación de un legado para la familia

[4,8]. Estas dimensiones, aunque difíciles de cuantificar, reflejan el valor ético y humanizador

de la TD, alineado con el enfoque de atención centrada en la dignidad propuesto por

Chochinov [30], que considera la identidad, la autonomía y la continuidad del ser como pilares

del cuidado compasivo al final de la vida.

La evidencia europea, particularmente el trabajo de Julião et al. [12] en Portugal, muestra que la TD no impacta en la supervivencia, pero sí en la reducción

del distrés psicológico y la mejora del bienestar emocional. Esto confirma que el

principal aporte de la TD radica en la esfera existencial, y refuerza la dignidad

y la autonomía del paciente al final de la vida.

Finalmente, debe reconocerse que la TD no reemplaza los cuidados médicos o psicosociales

convencionales, sino que los complementa, con el fin de potenciar la atención integral.

Su integración en protocolos de cuidados paliativos fortalecería el abordaje holístico,

especialmente en contextos latinoamericanos donde los valores familiares, espirituales

y culturales son determinantes en la vivencia de la enfermedad y la muerte [31].

5. Conclusiones

La TD se configura como una intervención viable, segura y bien aceptada en pacientes

con cáncer avanzado, con beneficios consistentes en los dominios emocional y existencial.

Sus efectos se manifiestan principalmente en la reducción de ansiedad y depresión,

el incremento de la esperanza y el fortalecimiento del bienestar espiritual, componentes

que repercuten en la calidad de vida y en el proceso de afrontamiento del final de

la vida.

Aunque los resultados cuantitativos sobre la dignidad percibida no fueron estadísticamente

significativos, la evidencia cualitativa y el consenso de los estudios revisados muestran

que la TD aporta valor clínico y humano, reafirma la identidad del paciente y contribuye

a una atención más compasiva y centrada en la persona.

La heterogeneidad metodológica, los tamaños muestrales reducidos y los sesgos identificados

limitan la generalización de los resultados; sin embargo, la coherencia entre hallazgos

cuantitativos y cualitativos sostiene la utilidad de la TD como intervención ética

y humanizadora en cuidados paliativos. En conjunto, la TD mejora la calidad del proceso

de morir al facilitar el cierre biográfico, la expresión de sentido y la preservación

del legado personal del paciente.

6. Recomendaciones

Se recomienda integrar la TD como parte complementaria de los programas de cuidados

paliativos, adaptando sus protocolos a la idiosincrasia cultural, espiritual y familiar

de cada población. La formación de profesionales en esta intervención dentro de equipos

interdisciplinarios contribuiría a fortalecer el modelo de atención integral y centrado

en la persona.

Asimismo, es necesario promover investigaciones multicéntricas y de mayor rigor metodológico

-particularmente ensayos clínicos aleatorizados con muestras amplias y seguimiento

longitudinal- que permitan confirmar los beneficios observados y explorar los mecanismos

de acción de la TD en distintos contextos clínicos y culturales.

Se sugiere incorporar enfoques mixtos (cuantitativos y cualitativos) que capten de

manera más completa los efectos de la intervención, dado que muchos de sus beneficios

trascienden lo medible. Finalmente, debe fomentarse la producción de evidencia en

América Latina, donde la TD ha demostrado gran aceptación y pertinencia cultural,

y donde su integración puede favorecer una atención más humana, compasiva y espiritual

en la etapa final de la vida.