1. Introduction

Metastases to the thyroid gland originating from solid tumors are an uncommon phenomenon

that requires different prognosis, diagnostic and therapeutic strategy than primary

thyroid carcinoma [1]. The main sites of origin are renal clear cell carcinoma (approximately 50%), lung

adenocarcinoma, gastrointestinal neoplasms, melanoma, and breast carcinoma [2,3]. This metastatic phenomenon can occur metachronously (60%), synchronously (34%),

or as the first manifestation of the underlying carcinoma (6%) [1,4].

These events represent between 0.13% and 2% of all thyroid malignancies, despite the

thyroid being the endocrine organ with the greatest blood supply, surpassed only by

the pancreas and adrenal glands [5,6]. Hypotheses related to the high blood flow and the high iodine and oxygen content,

which hinder tumor implantation and growth, have been proposed to explain its low

incidence. However, pre-existing thyroid diseases such as thyroiditis, adenomas, multinodular

goiter, or even primary thyroid cancer can create an environment conducive to metastatic

spread [7-9].

Diagnosis presents a significant challenge, especially in the absence of a primary

tumor, thus making immunohistochemistry (IHC) essential [3,4]. This series highlights metastases from renal cell carcinoma and breast cancer,

which, although rare, exemplify clinically and epidemiologically relevant cases due

to their diagnostic complexity and long latency periods. The average interval to the

appearance of thyroid metastases is 8.8 years for renal cell carcinoma and 9 years

for breast carcinoma [2,5,10]. Due to the scarcity of reports, particularly in breast cancer, this publication

seeks to define and distinguish the most used diagnostic studies for these two types

of malignant tumors and compare their therapeutic approach and prognosis within the

fields of oncology and endocrinology.

2. Clinical case 1

We present the case of a 69-year-old man with a history of hypertension and stage

III chronic kidney disease, who in 2017 underwent left radical nephrectomy for clear

cell renal carcinoma (pT1bN1M0, Fuhrman histological grade III). During oncological

follow-up, the patient remained asymptomatic, with a normal physical examination.

A positron emission tomography (PET-CT) scan incidentally revealed a hypometabolic

thyroid nodule (SUVmax [2,6]), prompting the recommendation for monitoring. Subsequently, in 2022, asymptomatic

primary hypothyroidism was diagnosed without palpable findings, and treatment with

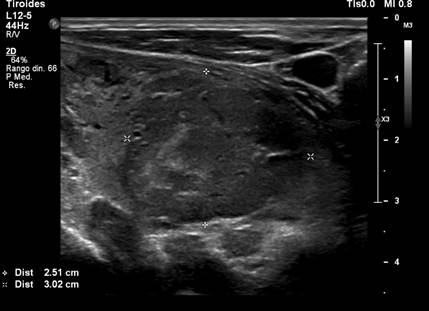

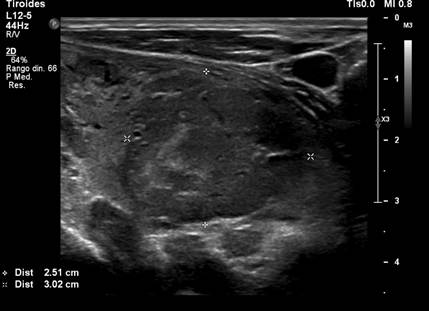

levothyroxine 50 mcg/day was initiated. Two years later, a cervical ultrasound revealed

a 3.5 x 2.5 x 3 cm hypoechoic solid nodule with irregular margins, cystic components,

and mixed vascularization, located in the lower pole of the left lobe, classified

as TIRADS 4C (Figure 1), which was palpable. A fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of the nodule was performed

and yielded a Bethesda category III.

Figure 1

Cervical ultrasound. Heterogeneous thyroid nodule measuring 3.5 x 2.5 x 3 cm.

Source: SOLCA Intranet - Guayaquil.

Histopathological study of the total thyroidectomy confirmed metastasis of clear cell

renal cell carcinoma, corroborated by immunohistochemistry (CAM 5.2 and PAX8 positive;

thyroglobulin, CK7, and TTF1 negative). PET-CT staging identified lymphadenopathy

in the left cervical region IV (23 mm, SUV LBM 4) and in the right cervical region

VI (20 mm, SUV LBM 4.8).

Subsequently, the Urological Tumor Committee prescribed systemic treatment with Sunitinib

50 mg, which had to be reduced to 25 mg daily due to toxicity (hand-foot syndrome

and thrombocytopenia). Following surgery, Levothyroxine was adjusted to 88 mcg/day,

achieving a TSH of 0.11 µIU/mL, thyroglobulin of 0.04 ng/mL, and undetectable antithyroglobulin

antibodies.

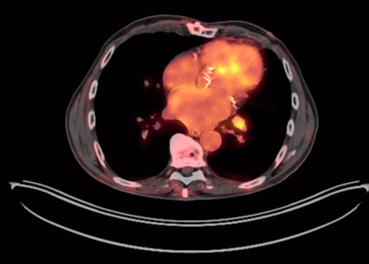

One year later, a follow-up PET-CT scan showed a decrease in the size and metabolism

of cervical lymph nodes; however, a pulmonary nodule was present in the left lower

lobe (13 mm), along with left hilar lymphadenopathy (12 mm), findings consistent with

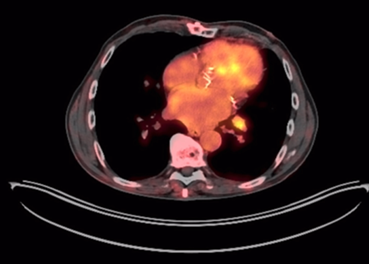

systemic tumor progression (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Thoracic PET-CT. Left hilar lymphadenopathy measuring 12 mm, hypermetabolic (SUV LBM

3), suggestive of metastatic origin.

Source: SOLCA Intranet - Guayaquil.

In accordance with the clinical course, second-line treatment with Axitinib 5 mg every

12 hours was initiated. As for the writing of this report, the patient remains in

good general clinical condition (Functional Status Scale grade 1; Karnofsky Performance

Status 90%), and under multidisciplinary follow-up.

3. Clinical case 2

A 49-year-old woman with a history of invasive ductal carcinoma of the right breast

(Grade 2, HER2+++, Ki-67: 60%), with T2N1M0 in 2017, treated with six cycles of docetaxel,

doxorubicin, and cyclophosphamide. In May 2021, following a one-month history of neck

pain, a neck CT scan revealed lymphadenopathy in the posterior triangle (11 mm). A

biopsy was taken, consistent with metastasis of the primary tumor. The patient was

subsequently treated with Pertuzumab, Trastuzumab, and Docetaxel, and later continued

with Letrozole 2.5 mg/day.

A PET-CT scan in December 2023 revealed persistent hypermetabolic lymphadenopathy

in the left lateral cervical region (SUVmax 2.4), as well as increased metabolism

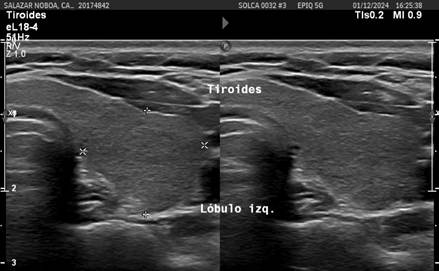

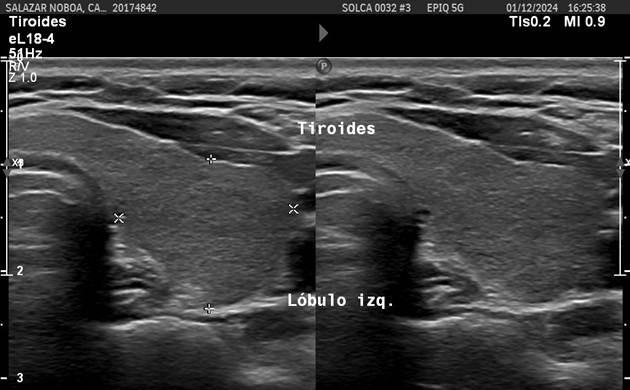

in the right thyroid lobe. A cervical ultrasound in December 2024 identified a 0.69

x 0.72 cm hypoechoic solid thyroid nodule, classified as TIRADS 4A (Figure 3). The fine-needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) was reported as Bethesda IV, and management

was decided upon with close monitoring.

Figure 3

Cervical ultrasound: Thyroid nodule classified as TIRADS 4A.

Source: SOLCA Intranet - Guayaquil.

In February 2025, cervical lymph node progression and diffuse hypermetabolic activity

in the thyroid were observed on PET-CT. Consequently, a total thyroidectomy with lymph

node dissection was performed, revealing two distinct neoplasms: thyroid metastasis

from breast carcinoma (IHC: Ki-67, HER2, PR, and GATA3 positive; TTF1 negative) and

a classic papillary thyroid microcarcinoma, follicular variant pT1a pN1a, in the right

lobe (0.2 cm; IHC: TTF1 and PAX8 positive).

For the microcarcinoma, ablative therapy with I-131 (180 mCi) was administered under

a hormonal withdrawal protocol, with a whole-body scan showing thyroid remnants, without

other iodine-sensitive lesions. Concurrently, for metastatic breast cancer, the patient

continues targeted therapy with dual anti-HER2 blockade (intravenous pertuzumab and

subcutaneous trastuzumab) plus oral capecitabine. At the time of data collection,

the patient remains in optimal general condition (ECOG 0) and under close follow-up.

4. Discussion

Thyroid gland metastases are infrequent; renal clear cell carcinoma is the most implicated.

The presence of thyroid cancer stem cells could explain this phenomenon, given their

role in therapeutic resistance and invasive capacity, interacting with the tumor microenvironment

and alterations in the MAPK and PI3K-Akt signaling pathways, which would favor neoplastic

progression and recurrence [8,11]. This mechanism may have contributed to the clinical course of the described cases,

particularly in breast carcinoma, where the coexistence of metastases promotes accelerated

progression [8,12].

Likewise, the latency period between the primary tumor and thyroid metastasis is often

prolonged due to the phenomenon of “metastatic dormancy,” in which tumor cells remain

inactive before reactivating their proliferation [11,12]. In the reported patients, thyroid metastasis was evident 7 and 8 years after the

diagnosis of renal and breast carcinoma, respectively. This is consistent with the

findings of Tjahjono R. et al., whose median was 92 months (7.6 years) [3,5,10]. From a diagnostic standpoint, these metastases pose a challenge, especially when

the primary tumor is unknown or subclinical. Although imaging techniques are useful,

they lack specificity in distinguishing between primary thyroid carcinoma and metastasis

[9,11,13]. In this context, immunohistochemistry (IHC) is essential for establishing a definitive

diagnosis. Specific markers, such as CD10, CA-IX, and PAX8 in renal cell carcinoma

enable determining its origin. This coincides with Stergianos S. et al., who documented

that 36% of metastatic thyroid tumors originated in the kidney (9,10). In the case

of breast carcinoma, the coexistence of lesions compatible with a primary thyroid

tumor (TTF-1 and TG positive) and ductal carcinoma metastases (GATA3 and estrogen

receptor positive) is an exceptional finding in the literature [1,6,14].

Regarding prognosis, the detection of thyroid metastases is usually associated with

low 5-year survival (<50%) [5]. However, surgical resection is associated with a better outcome in cases of oligometastases,

as observed in both patients who underwent total thyroidectomy and lymphadenectomy.

This may be supported by a retrospective study conducted by Tjahjono R. et al. in

Australia, where, although survival was higher in patients undergoing surgery with

systemic treatment (12 patients) compared to those managed only with systemic therapy/radiotherapy

(3 patients) (130 vs. 36 months), it was not statistically significant (p=0.208) due

to the study sample size and mortality resulting from cancer progression [1,5,6]. Furthermore, the use of tyrosine kinase inhibitors, such as Sunitinib and Axitinib

has shown efficacy in tumor reduction. This aligns with the findings of Tjahjono R.

et al., who demonstrated a median survival of 130 months with these drugs [3]. However, these agents are not free of complications observed with Sunitinib treatment

like toxicity, notably thyrotoxicosis, gastrointestinal toxicity, and hand-foot syndrome

[13]. Finally, in breast carcinoma metastases, hormonal blockade becomes relevant given

the expression of receptors, which can modify the dynamics of tumor dissemination

[15].

Current knowledge on thyroid gland metastases is very limited due to their rarity

and the scarcity of multicenter studies. However, future lines of research are proposed,

such as their application to metastasectomy in renal cell carcinoma [3] or the use of thyroid carcinoma stem cells, which interact with the tumor microenvironment,

to select the most appropriate treatment, thus improving treatment outcomes and prognosis

for these patients [8,11].

5. Conclusion

Thyroid metastases from solid tumors present a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge,

as evidenced by the cases described. These cases underscore the importance of long-term

follow-up in patients with a history of cancer due to the possibility of late recurrences

or unusual metastases. Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is established as a fundamental

tool for determining the tumor origin and guiding therapeutic management.

However, this series has significant limitations. By including only two cases, it

is not possible to make clinical generalizations or causal inferences, which reduces

external validity. Similarly, the lack of extensive clinical follow-up prevents the

evaluation of long-term outcomes. Finally, the coexistence of different neoplasms

in the thyroid gland highlights the biological complexity of cancer and reaffirms

the need for a multidisciplinary approach.

1. Introducción

Las metástasis hacia la glándula tiroides, originadas en tumores sólidos, constituyen

un fenómeno infrecuente que condiciona un pronóstico y una estrategia diagnóstica

y terapéutica distinta al carcinoma primario tiroideo [1]. Los principales sitios de origen son el carcinoma de células claras renales (aproximadamente

el 50 %), el adenocarcinoma de pulmón, neoplasias gastrointestinales, melanoma y,

menos frecuente, el carcinoma mamario [2, 3]. Este fenómeno metastásico puede ocurrir

de manera metacrónica (60 %), sincrónica (34 %) o como primera manifestación del carcinoma

subyacente (6 %) [1, 4].

Estos eventos representan entre el 0,13 % y el 2 % de todas las malignidades tiroideas,

a pesar de que la tiroides es un órgano endocrino con mayor irrigación sanguínea,

solo superado por el páncreas y las glándulas suprarrenales [5, 6]. Para explicar su baja incidencia se han planteado hipótesis relacionadas con el

elevado flujo sanguíneo y el alto contenido de yodo y oxígeno que dificultan la implantación

y crecimiento tumoral; no obstante, enfermedades tiroideas previas como tiroiditis,

adenomas, bocio multinodular o incluso cáncer tiroideo primario pueden favorecer un

ambiente propicio para la diseminación metastásica [7-9].

El diagnóstico representa un gran desafío, especialmente en ausencia de tumor primario

identificado, siendo esencial la inmunohistoquímica (IHQ) [3, 4]. En esta serie se destacan metástasis de carcinoma de células renales y de mama

que, aunque raras, ejemplifican casos de relevancia clínica y epidemiológica por su

alta complejidad diagnóstica y largas latencias. El intervalo promedio hasta la aparición

de metástasis tiroideas es de 8,8 años en carcinoma renal y de 9 años en carcinoma

mamario [2, 5, 10].

Debido a la escasez de reportes, en particular en cáncer de mama, esta publicación

tiene como objetivo definir y distinguir los estudios diagnósticos más empleados en

estos dos tipos de tumores malignos para contrastar su proceso terapéutico y pronóstico

en los ámbitos de la oncología y la endocrinología.

2. Caso clínico 1

Se presenta el caso de un hombre de 69 años con antecedentes de hipertensión arterial

y enfermedad renal crónica estadio iii, quien, en 2017, fue sometido a nefrectomía

radical izquierda por carcinoma renal de células claras (pT1bN1M0, grado histológico

Fuhrman iii). Durante el seguimiento oncológico permaneció asintomático, con exploración

física normal, y se le realizó una tomografía computarizada por emisión de positrones

(PET-CT) que evidenció de forma incidental un nódulo tiroideo hipometabólico (SUVmax)

[2, 6], motivo por el cual se indicó vigilancia.

Posteriormente, en 2022, se diagnosticó hipotiroidismo primario asintomático sin hallazgos

palpables y se inició tratamiento con levotiroxina 50 mcg/día. Dos años después, una

ecografía cervical reveló un nódulo sólido hipoecoico de 3,5 x 2,5 x 3 cm, con márgenes

irregulares, componentes quísticos y vascularización mixta, localizado en el polo

inferior del lóbulo izquierdo, clasificado como TIRADS 4C (Figura 1), el cual resultó palpable. Ante ello, se realizó una punción-aspiración con aguja

fina (PAAF) del nódulo con reporte Bethesda iii.

Figura 1

Ecografía cervical. Nódulo tiroideo heterogéneo de 3,5 x 2,5 x 3 cm

Fuente: Intranet SOLCA, Guayaquil.

El estudio anatomopatológico de la tiroidectomía total confirmó metástasis de carcinoma

renal de células claras, corroborada mediante inmunohistoquímica (CAM 5,2 y PAX8 positivos;

tiroglobulina, CK7 y TTF1 negativos). En la estadificación por PET-CT se identificaron

adenopatías en región cervical iv izquierda (23 mm, SUV LBM 4) y en región cervical

vi derecha (20 mm, SUV LBM 4,8).

Con posterioridad, el Comité de Tumores Urológicos indicó tratamiento sistémico con

sunitinib 50 mg, que debió reducirse a 25 mg diarios por toxicidad (síndrome mano-pie

y trombocitopenia). Tras la cirugía, se ajustó la levotiroxina hasta 88 mcg/día, alcanzando

TSH de 0.11 µUI/mL, tiroglobulina de 0.04 ng/mL y anticuerpos antitiroglobulina indetectables.

Un año después, en un control con PET-CT, se identificó disminución del tamaño y metabolismo

de las adenopatías cervicales; sin embargo, se presentaron un nódulo pulmonar en el

lóbulo inferior izquierdo (13 mm) y adenopatía hiliar izquierda (12 mm), hallazgos

compatibles con progresión tumoral sistémica (Figura 2).

Figura 2

PET-TC torácico. Adenopatía hiliar izquierda de 12 mm hipermetabólica (SUV LBM 3),

sugestiva de origen metastásico

Fuente: Intranet SOLCA, Guayaquil.

En concordancia con la evolución, se decidió iniciar tratamiento de segunda línea

con axitinib 5 mg cada 12 horas. Hasta la redacción del presente informe, el paciente

se mantiene con buen estado clínico general (Escala de estado funcional (ECOG) 1;

índice de Karnofsky 90 %) y bajo seguimiento multidisciplinario.

3. Caso clínico 2

Una mujer de 49 años con antecedente de carcinoma ductal infiltrante de mama derecha

(Grado 2, HER2+++, Ki-67: 60 %), con T2N1M0 en 2017, tratada con seis ciclos de docetaxel,

doxorrubicina y ciclofosfamida. En mayo de 2021, ante dolor cervical de un mes, se

realizó tomografía de cuello que evidenció adenopatía en triángulo posterior (11 mm),

con toma de biopsia compatible con metástasis del tumor primario, motivo por el cual

recibió pertuzumab, trastuzumab y docetaxel, manteniéndose posteriormente con letrozol

2,5 mg/día.

El PET-CT de diciembre de 2023 reveló persistencia de adenopatía hipermetabólica laterocervical

izquierda (SUVmax 2,4) e incremento metabólico en el lóbulo derecho tiroideo. Ulteriormente,

en la ecografía cervical de diciembre 2024, se identificó un nódulo tiroideo sólido

hipoecoico de 0,69 x 0,72 cm, clasificado como TIRADS 4A (Figura 3). La PAAF informó Bethesda iv, frente a lo que se decidió manejo mediante vigilancia

y control evolutivo.

Figura 3

Ecografía cervical: nódulo tiroideo clasificado como TIRADS 4A

Fuente: Intranet SOLCA, Guayaquil.

En febrero de 2025 se evidenció progresión ganglionar cervical y actividad hipermetabólica

difusa en tiroides en PET-CT. Ante ello, se efectuó tiroidectomía total con vaciamiento

ganglionar y se encontraron dos neoplasias distintas. Por un lado, metástasis tiroidea

de carcinoma mamario (IHQ: Ki-67, HER2, RP y GATA3 positivos; TTF1 negativo), y por

otro, un microcarcinoma papilar clásico de tiroides, variante folicular pT1a pN1a

en lóbulo derecho (0,2 cm; IHQ: TTF1 y PAX8 positivos).

Para el microcarcinoma se administró terapia ablativa con I-131 (180 mCi), bajo protocolo

de suspensión hormonal con rastreo corporal total que mostró remanentes tiroideos,

sin otras lesiones yodocaptantes. Paralelamente, para el cáncer de mama metastásico,

se mantiene en tratamiento dirigido con doble bloqueo anti-HER2 (pertuzumab intravenoso

y trastuzumab subcutáneo, más capecitabina oral).

Al momento de la recolección de datos, la paciente permanece en estado general óptimo

(ECOG 0) y en seguimiento estrecho.

4. Discusión

Las metástasis a glándula tiroides son infrecuentes, siendo el carcinoma de células

claras renales el más comúnmente implicado. La presencia de células madre cancerosas

tiroideas podría explicar este fenómeno, dado su papel en la resistencia terapéutica

y capacidad invasiva, en interacción con el microambiente tumoral y las alteraciones

en las vías de señalización MAPK y PI3K-Akt, lo que favorecería la progresión y recurrencia

neoplásica [8, 11]. Este mecanismo podría haber contribuido a la evolución clínica de los casos descritos,

particularmente en el carcinoma de mama, en el que la coexistencia de metástasis propició

una progresión acelerada [8, 12].

Asimismo, la latencia entre el tumor primario y la metástasis tiroidea suele ser prolongada

debido al fenómeno de dormancia metastásica, en el que células tumorales permanecen inactivas antes de reactivar su proliferación

[11, 12]. En los pacientes reportados, la metástasis tiroidea se evidenció a los 7 y 8 años

del diagnóstico de carcinoma renal y de mama, en concordancia con lo señalado por

Tjahjono et al., cuya mediana fue de 92 meses (7,6 años) [3, 5, 10].

Desde el punto de vista diagnóstico, estas metástasis constituyen un reto, sobre todo

cuando el tumor primario es desconocido o subclínico. Aunque las técnicas de imagen

son útiles, carecen de especificidad para distinguir entre carcinoma primario tiroideo

y metástasis [9, 11, 13]. En este contexto, la IHQ resulta esencial para establecer el diagnóstico definitivo.

Los marcadores específicos como CD10, CA-IX y PAX8 en carcinoma renal, permiten determinar

su origen, lo cual coincide con Stergianos et al., quienes documentaron que el 36 % de los tumores metastásicos en tiroides provenían

del riñón [9, 10]. En el caso de carcinoma mamario, la coexistencia de lesiones compatibles con tumor

tiroideo primario (TTF-1 y TG positivos) y metástasis de cáncer ductal (GATA3 y receptores

de estrógeno positivos) constituye un hallazgo excepcional en la literatura [1, 6, 14].

En cuanto al pronóstico, la detección de metástasis tiroideas suele relacionarse con

baja supervivencia a 5 años (<50 %) [5]. No obstante, la resección quirúrgica se asocia a mejor evolución en casos de oligometástasis,

como se observó en ambos pacientes intervenidos con tiroidectomía total y linfadenectomía.

Ello puede respaldarse en un estudio retrospectivo realizado por Tjahjono et al. en Australia, donde la supervivencia, a pesar de que fue mayor en los pacientes

sometidos a cirugía con tratamiento sistémico (12 pacientes), frente a los manejados

solo con terapia sistémica/radioterapia (tres pacientes) (130 vs. 36 meses), no fue

estadísticamente significativo (p = 0,208) por la muestra del estudio y su mortalidad

debido a la progresión oncológica [1, 5, 6].

Por otra parte, el uso de inhibidores de tirosina quinasa, como sunitinib y axitinib,

ha mostrado eficacia en la reducción tumoral, concordando con lo señalado por Tjahjono

et al., quienes evidenciaron una supervivencia media de 130 meses con estos fármacos [3]. Sin embargo, estos agentes no están exentos de toxicidad, destacando la tirotoxicosis,

la toxicidad gastrointestinal y el síndrome mano-pie, complicaciones observadas en

el tratamiento con sunitinib [13]. Finalmente, en metástasis de carcinoma mamario, el bloqueo hormonal adquiere relevancia

dada la expresividad de receptores, lo que puede modificar la dinámica de diseminación

tumoral [15].

El conocimiento actual sobre las metástasis a glándula tiroides es muy limitado por

su rareza y la escasez de estudios multicéntricos. Pese a esto, se proponen futuras

líneas de investigación como la aplicación sobre la metastasectomía en el carcinoma

de células renales [3] o el uso de las células madre del carcinoma de tiroides, que conllevan a interacciones

con el microambiente tumoral, para una selección del tratamiento más apropiado, mejorando

su resultado y el pronóstico de estos pacientes [8, 11].

5. Conclusión

Las metástasis a la glándula tiroides desde tumores sólidos, aunque poco frecuentes,

constituyen un desafío diagnóstico y terapéutico, tal como evidencian los casos descritos.

Estos subrayan la relevancia del seguimiento prolongado en pacientes con antecedentes

oncológicos, debido a la posibilidad de recurrencias tardías o metástasis inusuales.

La IHQ se establece como herramienta fundamental para precisar el origen tumoral y

orientar la conducta terapéutica.

No obstante, esta serie presenta limitaciones importantes, por ejemplo, al incluir

únicamente dos casos, no es posible realizar generalizaciones clínicas ni inferencias

causales, lo que reduce su validez externa. De igual manera, la ausencia de un seguimiento

clínico extenso impide evaluar desenlaces a largo plazo.

Finalmente, la coexistencia de distintas neoplasias en la glándula tiroides pone de

relieve la complejidad biológica del cáncer y reafirma la necesidad de un abordaje

multidisciplinario.