1. Introduction

It is estimated that 3-8% of patients diagnosed with breast cancer may be diagnosed

with metastatic disease [1]. The standard treatment for these cases is systemic therapy with significantly improved

OS and PFS, especially in patients with positive hormone receptors and/or HER2 [2,3].

Surgery has been conceived as a therapeutic approach aimed at relieving symptoms and

preventing complications associated with the local progression of the disease [3]. However, it has also been suggested that it has a beneficial effect in prolonging

patient OS through various mechanisms such as reduction of tumor load, elimination

of cancer stem cells, reversal of tumor-induced immunosuppression, reduction in clonal

heterogeneity, discontinuation of primary tumor self-seeding, interruption of multidirectional

tumor cell movement between primary and distant tumor sites, and decrease in tumor

promoter activities mediated by cancer stem cells [4].

As a result, the combined use of systemic therapy and surgical management in patients

with stage IV breast cancer has been investigated. RCTs report contradictory results

in terms of OS for those receiving both therapies [3,5-7], while retrospective studies, resulting from real-life experiences, show an improvement

in this parameter [3,8-12]. It provides relevant evidence in therapeutic decision-making.

Our research aims to describe the OS and PFS of patients with early-stage IV breast

cancer, who received CT and EST at a specialized cancer care center in Medellín -

Colombia.

2. Methods

An observational retrospective cohort study was carried out using information from

Fundación Colombiana de Cancerología Clínica Vida (FCCCV) database in Medellín, between

2013 and 2021. Data collection was carried out from 1 October 2022 to 15 January 2023.

Data of individuals who met the inclusion criteria were recorded, so the sample corresponded

to the total number of patients.

2.1. Patients

The inclusion criteria were: 1) Patients over 18 years of age with infiltrating stage

IV breast cancer at diagnosis; 2) Histological confirmation of primary disease; 3)

Clinical or imaging confirmation for metastatic disease; 4) Management with systemic

therapy only and/or local or regional surgery, considering any type of breast or axillary

surgery. 270 patients met the criteria and were reviewed. Exclusion criteria were

considered as follows: medical histories with more than 10% of the data lost, stage

IV disease by progression, pregnancy, lactation, metachronous breast cancer, and breast

cancer as second primary.

2.2. Variables

The primary result was OS calculated from the start of treatment to the last follow-up

or death from any cause. PFS was a secondary outcome calculated from the start of

treatment to the date of last follow-up or at which progress was documented.

Variables were evaluated in two groups of patients: exclusive systemic therapy and

combined therapy (systemic treatment plus breast and/or axillary surgery). Characteristics

of individuals at the time of diagnosis were collected in both groups: age, menopausal

status, and body mass index (BMI). The characteristics of the tumor were also recorded:

histological type and grade molecular subtype, tumor size, clinical and pathological

classification of regional nodules according to TNM classification [13], site and number of metastases, date, and site of first progression.

The date of diagnosis was the one described in the first study that documented the

disease remotely; if this information was not available, the date of the biopsy report;

and, if none of the previous were available, the data provided in the institution's

database. The date of progression of the disease for the first study was recorded.

Finally, the cutoff date for assessing the OS was 8 January 2023 via the Adres platform

(www.adres.gov.co/consulte-su-ep).

2.3. Statistical methods

A univariate analysis was carried out to characterize the study population. In the

case of quantitative variables, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test was applied

to determine whether they presented averages or medians. Qualitative variables were

determined using absolute and relative frequencies. Median survival was calculated

using the Kaplan Meier curve.

For bivariate analysis, survival associations with each factor were calculated independently;

for qualitative variables, chi square of independence; for quantitative variables,

student’s t-test or Mann-Whitney U test (quantitative - qualitative). The differences

in covariable survival were calculated using the Logrank test.

A multivariate analysis was performed to measure the association between covariables

and the event occurrence time using a Cox regression. A p value less than 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

As a sensitivity analysis of the possible effect of confounding by indication, a Propensity

Score analysis was performed using a logistic regression model, estimating the expected

effect throughout the sample. The probability difference is presented with its respective

confidence interval.

All analyses were carried out by the STATA software version 16.1.

3. Results

A total of 270 patients met the inclusion criteria, eight cases with unknown start

date were excluded, thus obtaining a final group of 262 patients: 174 receiving EST,

and 88 receiving CT.

Table 1

Demographic characteristics

|

Characteristic

|

Systemic treatment (N = 174)

|

Systemic + surgical treatment (N = 88)

|

P

|

|

Age, average ± Standard deviation

|

56.6 (13,4)

|

56.3 (14)

|

0.17

|

|

Menopausal status

|

|

|

|

|

Premenopausal

|

48 (27.6)

|

26 (29.5)

|

0.77

|

|

Postmenopausal

|

122 (70.1)

|

61 (69.3)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

4 (2.3)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Body mass index

|

|

|

|

|

Low weight:<18.5

|

18 (10.3)

|

6 (6.8)

|

0.19

|

|

Normal: 18.5 - 24.9

|

74 (42.5)

|

27 (30.7)

|

|

|

Overweight25 - 29.9

|

45 (25.9)

|

29 (33)

|

|

|

Obesity: > 30

|

17 (9.8)

|

14 (15.9)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

20 (11.5)

|

12 (13.6)

|

|

Characteristics of the disease are presented in Table 2. CT patients showed significantly more oligometastases and inflammatory tumors, while

EST patients had significantly higher bone, pleural, liver metastases, and T4b tumors.

The other characteristics were balanced.

Table 2

Characteristics of the disease

|

Characteristics

|

Systemic treatment (N = 174)

|

Systemic + surgical treatment (N = 88)

|

P

|

|

Laterality

|

|

|

|

|

Unilateral

|

165 (94.8)

|

83 (94.3)

|

0.53

|

|

Bilateral

|

9 (5.2)

|

5 (5.7)

|

|

Histological type

|

|

|

|

|

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma

|

144 (82.8)

|

81 (92)

|

0.26

|

|

Infiltrating lobular carcinoma

|

13 (7.5)

|

5 (5.7)

|

|

|

Mixed

|

2 (1.1)

|

0

|

|

|

Other

|

5 (2.9)

|

0

|

|

|

Occult carcinoma

|

3 (1.7)

|

0

|

|

|

Unknown

|

7 (4)

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

|

Histological grade

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

17 (9.8)

|

8 (9.1)

|

0.15

|

|

2

|

73 (42)

|

32 (36.4)

|

|

|

3

|

65 (37.4)

|

35 (39.8)

|

|

|

Occult carcinoma

|

6 (3.4)

|

0

|

|

|

Unknown

|

13 (7.5)

|

13 (14.8)

|

|

|

ER status

|

|

|

|

|

Positive

|

131 (75.3)

|

60 (68.2)

|

0.45

|

|

Negative

|

42 (24.1)

|

27 (30.7)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

1 (0.6)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

PR status

|

|

|

|

|

Positive

|

108 (62.1)

|

50 (56.8)

|

0.7

|

|

Negative

|

64 (36.8)

|

37 (42)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

2 (1.1)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Her 2 status

|

|

|

|

|

Positive

|

34 (19.5)

|

19 (21.6)

|

0.82

|

|

Negative

|

138 (79.3)

|

68 (77.3)

|

|

|

Equivocal, not FISH

|

1 (0.6)

|

0

|

|

|

Unknown

|

1 (0.6)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Ki 67, median + IQR

|

36.4 + 22

|

38.7 + 25.3

|

0.70

|

|

Subtype IHC

|

|

|

|

|

Luminal A

|

30 (17.2)

|

15 (17)

|

0.16

|

|

Luminal B

|

85 (48.9)

|

31 (35.2)

|

|

|

Triple negative

|

25 (14.4)

|

20 (22.7)

|

|

|

Luminal-HER2

|

18 (10.3)

|

13 (14.8)

|

|

|

HER2 positive

|

16 (9.2)

|

8 (9.1)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

0

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Number of metastases

|

|

|

|

|

<4

|

18 (10.3)

|

32 (36.4)

|

<0.001

|

|

>4

|

155 (89.1)

|

54 (61.4)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

1 (0.6)

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

|

Metastatic site

|

|

|

|

|

Bone

|

123 (70.7)

|

51 (58)

|

0.02

|

|

No

|

51 (29.3)

|

37 (42)

|

|

|

Lung

|

59 (33.9)

|

27 (30.7)

|

0.35

|

|

No

|

115 (66.1)

|

61 (69.3)

|

|

|

Liver

|

39 (22.4)

|

6 (6.8)

|

0.001

|

|

No

|

135 (77.6)

|

82 (93.2)

|

|

|

NCS

|

6 (3.4)

|

2 (2.3)

|

0.46

|

|

No

|

168 (96.6)

|

86 (97.7)

|

|

|

Distance

|

49 (28.2)

|

22 (25)

|

0.34

|

|

No

|

125 (71.8)

|

66 (75)

|

|

|

Pleural

|

19 (10.9)

|

4 (4.5)

|

0.06

|

|

No

|

155 (89.1)

|

84 (95.5)

|

|

|

Other

|

19 (10.9)

|

3 (13.6)

|

0.02

|

|

No

|

155 (89.1)

|

865 (96.6)

|

|

|

Tumor size

|

|

|

|

|

T1

|

4 (2.3)

|

2 (2.3)

|

0.02

|

|

T2

|

32 (18.4)

|

14 (15.9)

|

|

|

T3

|

19 (10.9)

|

13 (14.8)

|

|

|

T4a

|

2 (1.1)

|

5 (5.7)

|

|

|

T4b

|

80 (46)

|

34 (38.6)

|

|

|

T4C

|

5 (2.9)

|

3 (3.4)

|

|

|

T4d

|

17 (9.8)

|

17 (19.3)

|

|

|

TX

|

9 (5.2)

|

0

|

|

|

Unknown

|

6 (3.4)

|

0

|

|

|

Focality

|

|

|

|

|

Unifocal

|

157 (90.2)

|

81 (92)

|

0.17

|

|

Multifocal

|

7 (4)

|

3 (3.4)

|

|

|

Multicentric

|

3 (1.7)

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

|

Multifocal and multicentric

|

0

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

|

Occult

|

5 (2.9)

|

0

|

|

|

Unknown

|

2 (1.1)

|

0

|

|

|

Clinical N

|

|

|

|

|

N1

|

58 (33.3)

|

29 (33.3)

|

0.16

|

|

N2

|

58 (33.3)

|

28 (31.8)

|

|

|

N3

|

29 (16.7)

|

24 (27.3)

|

|

|

N0

|

14 (8)

|

6 (6.8)

|

|

|

Nx

|

8 (4.6)

|

0

|

|

|

Unknown

|

7 (4.1)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

When evaluating the treatment characteristics, significant differences between groups

were found in almost all the variables. Thus, CT patients presented significantly

higher requirements for cytotoxic therapy, polychemotherapy, and the use of Anthracycline

drugs with taxans. While patients with EST received significantly more endocrine therapy

with aromatase inhibitors (AI) and the combination of AI with cyclin-dependent kinase

inhibitor (CDKI). Radiation therapy was administered significantly more in the CT

group. There were no differences between the groups regarding the use of anti-Her

therapy and suppression of ovarian function. (Table 3).

Characteristics of surgical treatment are presented in Table 4.

Table 3

Characteristics of the treatment

|

Characteristics

|

Systemic treatment (N = 174)

|

Systemic + surgical treatment (N = 88)

|

P

|

|

Cytotoxic therapy

|

|

|

|

|

Monochemotherapy

|

61 (35.1)

|

20 (22.7)

|

0.002

|

|

Polychemotherapy

|

70 (40.2)

|

56 (63.6)

|

|

|

No CT/do not accept

|

43 (24.7)

|

12 (13.6)

|

|

|

Chemotherapy drug

|

|

|

|

|

Taxans

|

53 (30.5)

|

13 (14.8)

|

0.001

|

|

Anthracyclines

|

14 (8)

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

|

Platinum

|

0

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Capecitabine

|

1 (0.6)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Taxans and platinum

|

10 (5.7)

|

7 (8)

|

|

|

Taxans y Anthracyclines

|

38 (21.8)

|

40 (45.5)

|

|

|

Taxans and others

|

6 (3.4)

|

3 (3.4)

|

|

|

Antracyclic and others

|

2 (1.1)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Platinum and others

|

1 (0.6)

|

0

|

|

|

Taxans, anthracyclines and platinum

|

3 (1.7)

|

3 (3.4)

|

|

|

Others

|

3 (1.7)

|

6 (6.8)

|

|

|

Do not require

|

43 (24.7)

|

11 (12.5)

|

|

|

Endocrine Therapy

|

|

|

|

|

Tamoxifen

|

16 (9.2)

|

17 (19.3)

|

0.01

|

|

Aromatase inhibitor

|

60 (34.5)

|

26 (29.5)

|

|

|

Fulvestrant

|

4 (2.3)

|

5 (5.7)

|

|

|

Cycline and aromatase inhibitor

|

37 (21.3)

|

6 (6.8)

|

|

|

Cycline and fulvestrant inhibitor

|

2 (1.1)

|

0

|

|

|

Fulvestran anastrozole

|

1 (0.6)

|

0

|

|

|

Do not receive

|

11 (6.3)

|

4 (4.5)

|

|

|

Do not require

|

43 (24.7)

|

30 (34.1)

|

|

|

Suppression of ovarian function

|

|

|

|

|

Surgical

|

19 (10.9)

|

7 (8)

|

0.47

|

|

Medicine

|

6 (3.4)

|

6 (6.8)

|

|

|

Radiotherapy

|

3 (1.7)

|

3 (3.4)

|

|

|

Do not receive

|

8 (4.6)

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

|

Do not require

|

138 (79.3)

|

70 (79.5)

|

|

|

Anti HER2 Therapy

|

|

|

|

|

Trastuzumab

|

10 (5.7)

|

10 (11.4)

|

0.4

|

|

Pertuzumab

|

2 (1.1)

|

0

|

|

|

Tratuzumab + Pertuzumab

|

25 (14.4)

|

12 (13.6)

|

|

|

Do not receive

|

1 (0.6)

|

0

|

|

|

Do not require

|

136 (78.2)

|

66 (75)

|

|

|

Locoregional radiotherapy

|

|

|

|

|

Breast

|

7 (4)

|

2 (2.3)

|

<0.001

|

|

Breast and locoregional nodules

|

5 (2.9)

|

6 (6.8)

|

|

|

Rib cage

|

0

|

8 (9.1)

|

|

|

Rib cage and y locoregional nodules

|

0

|

9 (10.2)

|

|

|

Axial

|

1 (0.6)

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

|

Do not receive

|

156 (89.7)

|

35 (39.8)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

5 (2.9)

|

27 (30.7)

|

|

|

Radiotherapy to metastasis

|

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

70 (40.2)

|

21 (23.9)

|

0.04

|

|

No

|

102 (58.6)

|

67 (76.1)

|

|

|

Unknown

|

2 (1.2)

|

0

|

|

Table 4

Surgical and systemic treatment characteristics

|

Characteristics

|

Systemic + surgical treatment (N = 88)

|

|

Average N positive by pathology

|

5.3 + 6.2

|

|

First management

|

|

|

Systemic

|

78 (88.6)

|

|

Surgical

|

10 (11.4)

|

|

Cause of surgery

|

|

|

Hygienic

|

24 (27.3)

|

|

Systemic but non-local response, albeit stable

|

21 (23.9)

|

|

Complete clinical response

|

11 (12.5)

|

|

No systemic or local response

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

Stable systemic disease and local progression

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

Others

|

10 (11.4)

|

|

Unknown

|

20 (22.7)

|

|

Type of Surgery

|

|

|

Modified radical mastectomy

|

71 (80.7)

|

|

Simple mastectomy

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

Conservative surgery and axillary dissection

|

10 (11.4)

|

|

Conservative surgery

|

1 (1.1)

|

|

Conservative surgery and sentinel ganglion biopsy

|

2 (2.3)

|

|

Axillary dissection

|

2 (2.2)

|

4. Survival analysis

The 262 patients provided a total of 6910.92 months of follow-up with an average of

58.38 months (range 48.6 - 68 months) and a median of 36.17 months (95% CI 26.91-45,42).

4.1. Progression-free survival

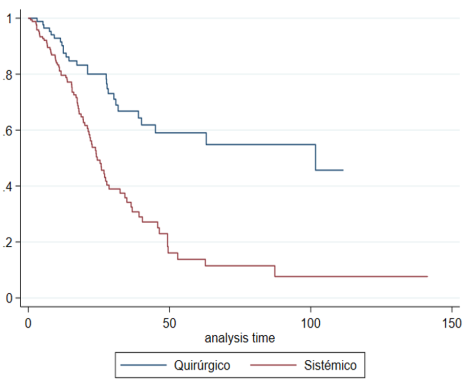

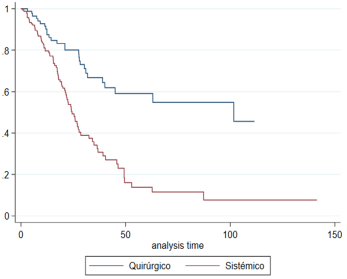

114 progression events occurred, 85 in the EST group and 29 in the CT group. The average

PFS in the EST group was 38.56 months (range 29.89-47.24); while for the CT group

it was 72.25 (rang 60.92.83.37), i.e., a statistically significant result (p<0.001)

(Figure 1A).

PFS at the year of diagnosis was 79.6% (95% CI 72.2-85.2%) and 90.2% (95 % CI 81.4-95%);

at 5 years of age 11.5% (4.6-21.8% CI 95%) and 54.6% (30.8-67.9%) for EST vs. CT,

respectively.

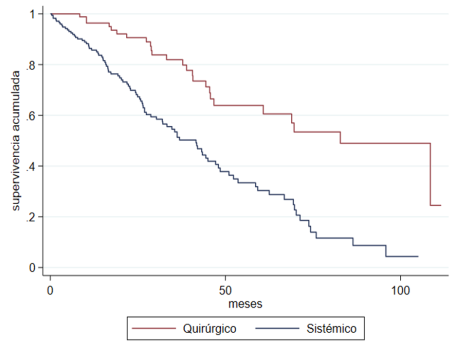

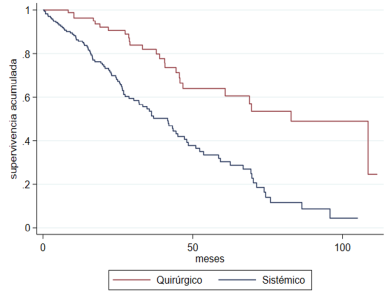

4.2. Overall survival

118 deaths occurred, 92 in the EST group and 26 in the CT group. The median OS for

the entire population was 48.63 months (95% CI 40.43-56.82): for the EST group, it

was 42.4 months (93% CI 95% 33, 23-51.56); and for the CT group, 82.33 (95 % CI 62.1-102.55),

i.e., a statistically significant difference (p<0.001) (Figure 1B).

OS at the year of diagnosis was 85.7% (CI 95 %: 79.4-90,2%) and 96.4% (CI 95%: 89.1-98.8%).

After 5 years of follow up, OS was 30% with 95% CI 20.8-39.7% and 59.9% with 95% CI

44.5-72.2% for the EST group and the CT group, respectively.

Fig. 1A

Progression free survival according to treatment group

Fig. 1B

overall survival according to treatment group

4.3. Confounding Factor Adjustment

Based on the results of the study and data from the literature, we considered as confounding

variables for adjustment: age, menopausal status, tumor size, site of metastasis,

number of metastases, status of hormone and HER2 receptors, molecular subtype, cytotoxic

and endocrine systemic management.

The PFS shows an unadjusted analysis with HR 0.34 CI 95 % 0.22-0.52 (p<0.001) and

the OS of 0.33 CI 95% 0.21-0.52 (p <0.001) (Table 5).

Table 5

Crude analysis of progression free survival and overall survival

|

Observed estimate

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Progression free survival

|

|

|

Overall survival

|

|

|

|

|

HR

|

CI95%

|

P value

|

HR

|

CI95%

|

P value

|

|

Type of treatment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Systemic

|

Ref.

|

|

|

Ref

|

|

|

|

Surgical + systemic

|

0.34

|

0.22 - 0.52

|

<0.001

|

0.33

|

0.21 - 0.52

|

<0.001

|

The adjusted results can be seen in Table 6, showing that for both PFS and OS there is a statistically significant association

in favor of CT. In the adjusted estimates, PFS showed a significant association with

triple-negative subtype, the presence of liver metastasis and tumor size, T4b being

of higher risk. Although T4a, T4d, and Tx showed significant results, the patient

group for each of these categories was small and the confidence intervals wide. The

same occurred with endocrine management and the use of CDKI and fulvestrant. As for

the clinical staging of the nodules, confidence intervals for these categories were

also wide.

Table 6

Adjusted analysis of Progression free survival and Overall Survival

|

|

Adjusted estimates

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Progression free survival

|

|

|

|

Overall survival

|

|

|

|

|

|

HR

|

CI95%

|

|

P value

|

HR

|

CI95%

|

|

P value

|

|

Type of treatment

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Systemic

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Surgical + systemic

|

0.28

|

0.16 - 0.5

|

|

<0.001

|

0.23

|

0.13 - 0.43

|

|

<0.001

|

|

Molecular Subtype

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Her 2

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Luminal A

|

1.3

|

0.2

|

9.4

|

0.814

|

6.8

|

1.0

|

48.3

|

0.056

|

|

Luminal B

|

4.5

|

0.7

|

29.3

|

0.116

|

29.7

|

4.7

|

189.0

|

<0.001

|

|

Triple negative

|

3.5

|

1.3

|

9.1

|

0.010

|

13.3

|

4.9

|

36.1

|

<0.001

|

|

Luminal - Her 2

|

2.6

|

0.4

|

16.6

|

0.313

|

3.9

|

0.6

|

23.6

|

0.138

|

|

Liver Metastasis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Yes

|

2.2

|

1.2

|

4.0

|

0.009

|

1.6

|

0.9

|

2.7

|

0.078

|

|

Number of metastasis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1-3 metastasis

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

> 4 metastasis

|

2.4

|

1.2

|

4.8

|

0.016

|

1.7

|

0.9

|

3.3

|

0.117

|

|

Ct stage

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

T2

|

5.2

|

1.4

|

19.5

|

0.015

|

6.3

|

1.2

|

33.3

|

0.030

|

|

T3

|

4.3

|

0.9

|

19.3

|

0.059

|

8.9

|

1.6

|

50.8

|

0.014

|

|

T4a

|

9.3

|

1.3

|

67.1

|

0.027

|

62.3

|

8.4

|

461.6

|

<0.001

|

|

T4b

|

4.7

|

1.2

|

18.2

|

0.023

|

10.8

|

2.1

|

56.7

|

0.005

|

|

T4c

|

34.2

|

5.6

|

207.9

|

<0.001

|

61.2

|

8.6

|

434.9

|

<0.001

|

|

T4d

|

4.5

|

1.2

|

17.9

|

0.030

|

10.7

|

2.0

|

57.6

|

0.006

|

|

Tx

|

15.1

|

2.1

|

108.4

|

0.007

|

4.2

|

0.3

|

51.4

|

0.263

|

|

Cn stage

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nx

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

N1

|

8.8

|

1.7

|

47.1

|

0.011

|

1.3

|

0.3

|

6.1

|

0.774

|

|

N2

|

14.3

|

2.7

|

76.4

|

0.002

|

2.1

|

0.4

|

10.1

|

0.359

|

|

N3

|

20.1

|

3.5

|

114.0

|

0.001

|

1.8

|

0.3

|

9.1

|

0.487

|

|

N0

|

7.8

|

1.2

|

50.3

|

0.032

|

1.4

|

0.2

|

7.9

|

0.704

|

|

Type of chemotherapy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Polychemotherapy

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Monochemotherapy

|

1.6

|

1.0

|

2.7

|

0.057

|

1.6

|

1.0

|

2.7

|

0.067

|

|

Did not receive

|

1.1

|

0.6

|

2.3

|

0.700

|

1.8

|

0.9

|

3.4

|

0.077

|

|

Initial endocrine therapy

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

AI+ CDKI

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Tamoxifen

|

2.5

|

1.0

|

6.6

|

0.060

|

1.3

|

0.5

|

3.7

|

0.622

|

|

AI

|

2.3

|

1.0

|

5.3

|

0.052

|

1.8

|

0.8

|

4.2

|

0.176

|

|

Fulvestrant

|

3.5

|

1.0

|

11.9

|

0.042

|

2.7

|

0.8

|

9.2

|

0.111

|

|

CDKI +Fulvestrant

|

17.8

|

3.2

|

97.9

|

0.001

|

NE

|

|

|

|

|

Fulvestrant + AI

|

NE

|

|

|

|

NE

|

|

|

|

In the adjusted estimates for OS, significant associations were found in luminal B

subtypes, triple-negative, and tumor staging; however, when reviewing the confidence

intervals, they were all very wide.

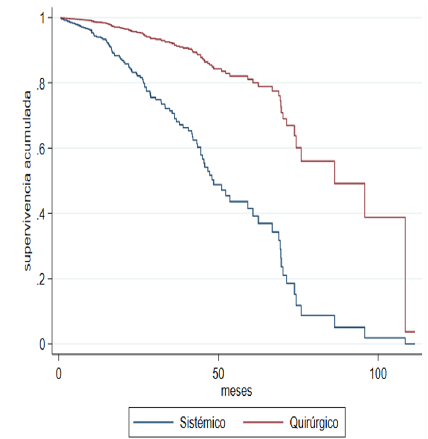

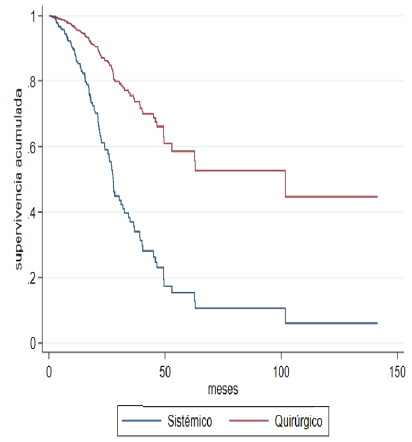

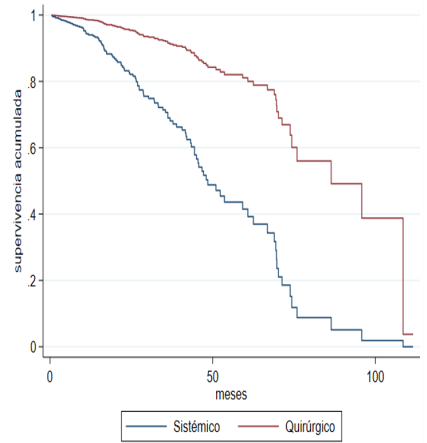

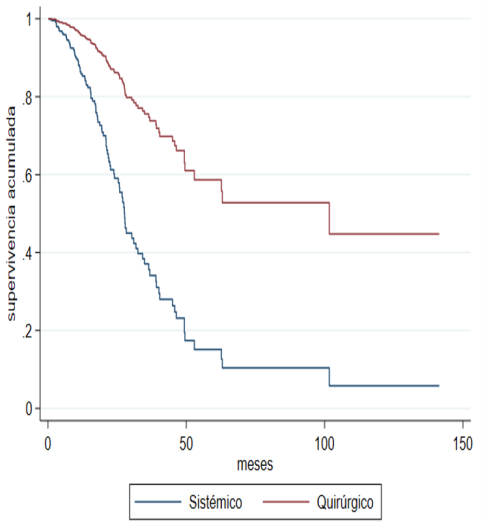

When the sensitivity analysis is carried out by the propensity score considering the

characteristics that differed significantly between the groups by indication of treatment

(pre-T, number of metastases, and site of the metastasis), the adjusted progression-free

survival curves (Figure 2A) and global (Figure 2B) are drawn, and the significant difference in favor of joint management in terms

of OS and PFS continues to be observed.

Fig. 2A

Adjusted Overall Survival

Fig. 2B

Adjusted Progression-Free Survival

5. Discussion

Stage IV breast cancer is a heterogeneous and incurable disease, its management is

aimed at prolonging survival and palliation of symptoms, systemic therapy being the

main pillar. However, multiple studies have been conducted to assess whether CT offers

any additional benefit in oncological outcomes. The present study looked at this group

of patients as well as those treated with EST.

Our study population had an average age of 56 years and a predominance of menopausal

patients, consistent with what is in the literature. Nationally, Diaz and Cols had

an average age of 58.8 years and a 62.9% postmenopausal [14]. And international studies, in general, report an average age of >50 years [1, 6 - 9, 15- 18] and most menopausal patients [5, 7, 12, 17].

The main type of carcinoma in our cohort was the infiltrating subtype, moderate to

high grade, hormone-positive, ductal, which is consistent with the global literature

[6 -9,11,14,17-19]. However, the triple negative subgroup, which has the lowest occurrence in various

studies [6,7,12], took the second place in our cohort. Both in the literature and in our study, tumors

were mainly classified at stage T4 [6, 8, 11, 14,16, 20]. Although, Soran and Cols [6] and Thomas and Colls [18] reported a higher frequency of small T2 stage tumors in their clinical trials.

Most of our patients received EST as in many of the retrospective studies [8, 11,

16-18]; this is supported by research results showing that surgical treatment is not

associated with a higher rate of OS [1, 7, 12, 19]. It is important to note the clinical trial E2108 [7], where they randomized 256 patients to EST and CT, allowed the use of contemporary

systemic therapies and showed the absence of effect on OS; thus, a better locoregional

control in the CT group.

Our research showed that there were better results in OS and PFS in patients with

CT, even after adjusting confounding variables. This is consistent with the findings

of several retrospective descriptive studies and even an RCT [6, 8, 11, 12, 14-19]. The survival benefits of locoregional surgery in stage IV patients are supported

in multiple hypotheses: some studies suggest that index lesion may behave as a reservoir

of sick stem cells and removing it would decrease the likelihood of developing new

sites of distant disease [21]. Resection of the primary tumor can increase angiogenesis by sensitizing it to chemotherapy

and facilitating the entry of the drug into cancer cells [22,23]. Removing necrotic and tumor tissue eliminates chemoresistant tissues, restores host

immunocompetence, and reduces growth of metastases [24, 25] thus resulting in increased patient survival [26]. Although there is the hypothesis

that surgery in this group of patients may stimulate the progression of the disease

by increased release of local growth factors [27], these can accelerate the proliferation of circulating tumor cells in peripheral

blood and affect the OS and PFS [24, 25, 28-30].

In several studies [6, 8, 14, 17] including ours, hormone receptor status was as an independent prognosis factor, suggesting

that tumor biology is important in survival. In contrast, there are also reports where

sub-group tests of the hormone receptor status or HER2 show no benefit in OS [7].

Polymetastatic disease characterized our population as in a previous Colombian study

[14] and in the RCT [1,6,7]. The metastatic pattern, both in number and location of distant disease, has also

been identified as an independent and significant variable for patient survival outcomes

[6,9-12,15,17]. Soran and Cols [6] identified that patients with solitary bone metastasis undergoing surgery had a significant

benefit in OS compared to those who did not undergo surgery, although in their multivariate

analysis, that association proved to be marginal. Rapiti and Cols [10] informed that the surgical effect on survival was not different for patients with

bone metastases vs. other sites; however, after stratification, they observed a positive

effect of surgery with negative margins in those who had bone metastases exclusively.

Moreover, there are also studies where survival did not differ according to the treatment

independent of the metastasis pattern [1, 7, 12]. For instance, Badwe and Cols [1] concluded that surgical management had no impact on patient survival, but also did

not identify any subgroup of patients likely to benefit from locoregional treatment.

Our study found a significant association, with worse PFS, in those patients who had

liver metastases and metastasis number >4, whereas OS showed no association with these

variables.

As in the literature, the most widely used systemic treatment in our population was

chemotherapy [1-9, 12,15-18, 20]. Non-administration of systemic therapy, when indicated, occurs in some retrospective

studies [8, 9, 14, 16, 17], including at the Tata Memorial Hospital in India [1]. In the RCT, treatment with taxans and antiHER2 was limited to only a small number

of patients, thereby affecting their survival results. This is not our case, the patients

received almost entirely the indicated therapies, allowing us to observe the real

impact of local control on the patient’s survival with protocol management.

Due to the retrospective nature of the study, one of its limitations is the lack of

randomization and thus the possible bias of selection for the treatment groups, this

would explain the beneficial effect in OS and PFS in patients receiving CT. Retrospective

studies showed that patients who underwent surgery had better prognostic characteristics

[30-33] and some had responded to systemic treatment, which could then be the causes of better

survival and not the surgical procedure itself [12]. In our study, patients undergoing surgery had a higher tumor load; it was also observed

that when grouping surgical indications, most of them presented a complete or partial

response to systemic therapy, leading us to consider that the benefit would be associated

with systemic treatment. Similarly, the sample size is low, which does not allow us

to establish a clinical recommendation.

As for the clinical records, some patients lacked information about their management,

most evident in the early years. However, those were excluded so that they did not

affect the results.

6. Conclusion

In patients with metastatic breast cancer at debut, the additional benefit that locoregional

surgical management can offer is controversial. The higher quality RCT argues that

locoregional control does not offer a better OS, while retrospective studies, resulting

from real-life experiences, like our research, report a benefit with surgical management.

1. Introducción

Del 3 al 8 % de los pacientes diagnosticados con cáncer de mama pueden debutar con

enfermedad metastásica [1]. El tratamiento estándar para estos casos es la terapia sistémica con la que se han

mejorado significativamente la supervivencia global (SG) y la supervivencia libre

de progresión (SLP), especialmente en aquellas pacientes con receptores hormonales

o Her 2 positivo [2,3].

Actualmente, la cirugía se ha concebido con un enfoque terapéutico complementario,

con el objetivo de paliar los síntomas y prevenir las complicaciones asociadas a la

progresión local de la enfermedad [3]. Sin embargo, se ha sugerido también que tiene un potencial efecto benéfico para

prolongar la SG de los pacientes a través de diversos mecanismos, como la reducción

de la carga tumoral, la eliminación de células madre cancerosas, la reversión de la

inmunosupresión inducida por el tumor, la reducción de la heterogeneidad clonal, la

interrupción de la autosiembra del tumor primario, la interrupción del movimiento

multidireccional de células tumorales entre el tumor primario y sitios distantes y

la reducción de las actividades promotoras de tumores mediadas por las células madre

cancerígenas [4].

Por lo anterior, el uso conjunto del manejo sistémico y quirúrgico en pacientes con

cáncer de mama estadio IV ha sido objeto de investigación. Los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados

(ECA) reportan resultados contradictorios en cuanto a la SG de quienes reciben ambas

terapias [3,5-7], mientras que los estudios retrospectivos, resultantes de experiencias en condiciones

reales, muestran una mejoría en este parámetro [3,8-12], lo que proporciona así evidencia relevante en la toma de decisiones terapéuticas.

Sumada a los estudios anteriores, esta investigación tuvo como objetivo describir

la SG y la SLP de pacientes con cáncer de mama estadio IV inicial, que recibieron

terapia conjunta (TC) y terapia sistémica exclusiva (TSE) en un centro de referencia

oncológico de la ciudad de Medellín, Colombia.

2. Metodología

Se realizó un estudio observacional de cohorte retrospectivo, tomado de la base de

datos de la Fundación Colombiana de Cancerología Clínica Vida de Medellín, entre 2013

y 2021. La recolección de los datos se realizó desde el 1.o de octubre del 2022 hasta el 15 de enero del 2023. Se registraron los datos de las

personas que cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión, por lo que la muestra correspondió

al total de pacientes.

2.1. Pacientes

Los siguientes son los criterios de inclusión para el estudio: 1) pacientes mayores

de 18 años con cáncer de mama infiltrante estadio IV al diagnóstico, 2) confirmación

histológica de la enfermedad primaria, 3) confirmación clínica o paraclínica de la

enfermedad metastásica, 4) manejo con terapia sistémica sola o con cirugía local o

regional, se consideró cualquier tipo de intervención quirúrgica en la mama o axila.

Se revisaron 270 historias de pacientes que cumplían con dichos criterios. Se consideraron

los siguientes criterios de exclusión: historias con más del 10 % de los datos perdidos,

enfermedad estadio IV por progresión, embarazo, lactancia, cáncer de mama metacrónico

y cáncer de mama como segundo primario.

2.2. Variables

La variable resultado principal fue la SG calculada desde el inicio del tratamiento

hasta el último seguimiento o muerte por cualquier causa. La SLP fue una variable

resultado secundario que se calculó desde el inicio del tratamiento hasta la fecha

del último seguimiento o en la que se documentó progresión.

Las variables se evaluaron en dos grupos de pacientes: manejo sistémico exclusivo

y manejo conjunto (tratamiento sistémico más quirúrgico mamario o axilar). En ambos

grupos se recopilaron las características de los individuos al momento del diagnóstico:

edad, estado de la menopausia e índice de masa corporal (IMC). También se registraron

las características del tumor: tipo y grado histológico, subtipo molecular, tamaño

tumoral, clasificación clínica y patológica de los ganglios regionales de acuerdo

con la clasificación TNM [13], sitio y número de metástasis, fecha y sitio de la primera progresión.

La fecha del diagnóstico correspondió a la descrita en el primer estudio de extensión

que documentó la enfermedad a distancia; si esta información no estaba disponible,

se registró la fecha del reporte de biopsia que informó el cáncer, y si no se contaba

con ninguna de las anteriores, se usó la fecha suministrada en la base de datos de

la institución. Para la fecha de progresión de la enfermedad se registró la del primer

estudio que la documentó. Finalmente, la fecha de corte para evaluar la SG fue el

8 de enero del 2023 a través de la plataforma Adres (www.adres.gov.co/consulte-su-ep).

2.3. Métodos estadísticos

Se realizó un análisis univariado para caracterizar a la población de estudio. En

el caso de las variables cuantitativas se aplicó la prueba de normalidad de Kolmogorov-Smirnov,

para definir si se presentaban con promedios o medianas. Las variables cualitativas

se presentaron usando frecuencias absolutas y relativas. La mediana de la supervivencia

se calculó mediante la curva de Kaplan-Meier.

Para el análisis bivariado se calcularon las asociaciones con respecto a la supervivencia

con cada uno de los factores de manera independiente. Para el caso de las variables

cualitativas con ji al cuadrado de independencia y para las cuantitativas se calculó

con la prueba t de student o U de Mann-Whitney (cuantitativa-cualitativa). Las diferencias

en la supervivencia según covariables se calcularon con la prueba de log Rank test.

Se realizó un análisis multivariado para medir la asociación entre covariables y el

tiempo a la presentación del evento mediante una regresión de Cox. Un valor de p inferior

a 0,05 se consideró estadísticamente significativo.

Como análisis de sensibilidad del posible efecto de confusión por indicación se realizó

un análisis por propensity score con un modelo de regresión logística, estimando el efecto esperado en toda la muestra.

La diferencia de probabilidades se presenta con su respectivo intervalo de confianza.

Todos los análisis se realizaron en el programa STATA versión 16.1.

3. Resultados

Un total de 270 pacientes, todas mujeres, cumplieron con los criterios de inclusión.

Se excluyeron ocho casos porque se desconocía la fecha de inicio del tratamiento,

lo que dejó un grupo final de 262 pacientes; 174 recibieron TSE y 88, TC.

La Tabla 1 muestra que los grupos de manejo estaban balanceados por sus características demográficas.

Tabla 1

Características demográficas

|

Características

|

Tratamiento sistémico (N = 174)

|

Tratamiento sistémico + quirúrgico (N = 88)

|

P

|

|

Edad, media ± desviación estándar

|

56,6 (13,4)

|

56,3 (14)

|

0,17

|

|

Estado menopáusico

|

|

|

|

|

Premenopáusicas

|

48 (27,6)

|

26 (29,5)

|

0,77

|

|

Posmenopáusicas

|

122 (70,1)

|

61 (69,3)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

4 (2,3)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Índice de masa corporal

|

|

|

|

|

Bajo peso: < 18,5

|

18 (10,3)

|

6 (6,8)

|

0,19

|

|

Normal: 18,5-24,9

|

74 (42,5)

|

27 (30,7)

|

|

|

Sobrepeso: 25-29,9

|

45 (25,9)

|

29 (33)

|

|

|

Obesidad: > 30

|

17 (9,8)

|

14 (15,9)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

20 (11,5)

|

12 (13,6)

|

|

Las características de la enfermedad se reportan en la Tabla 2. Las pacientes del TC presentaron significativamente más oligometástasis y tumores

inflamatorios, mientras que las pacientes de TSE tenían significativamente más metástasis

óseas, pleurales y hepáticas, además de tumores T4b. Las demás características se

encontraban balanceadas.

Tabla 2

Características de la enfermedad

|

Características

|

Tratamiento sistémico (N = 174)

|

Tratamiento sistémico + quirúrgico (N = 88)

|

P

|

|

Lateralidad

|

|

|

|

|

Unilateral

|

165 (94,8)

|

83 (94,3)

|

0,53

|

|

Bilateral

|

9 (5,2)

|

5 (5,7)

|

|

|

Tipo histológico

|

|

|

|

|

Carcinoma ductal infiltrante

|

144 (82,8)

|

81 (92)

|

0,26

|

|

Carcinoma lobular infiltrante

|

13 (7,5)

|

5 (5,7)

|

|

|

Mixto

|

2 (1,1)

|

0

|

|

|

Otro

|

5 (2,9)

|

0

|

|

|

Cáncer oculto

|

3 (1,7)

|

0

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

7 (4)

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

|

Grado histológico

|

|

|

|

|

1

|

17 (9,8)

|

8 (9,1)

|

0,15

|

|

2

|

73 (42)

|

32 (36,4)

|

|

|

3

|

65 (37,4)

|

35 (39,8)

|

|

|

Oculto

|

6 (3,4)

|

0

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

13 (7,5)

|

13 (14,8)

|

|

|

Estado RE

|

|

|

|

|

Positivo

|

131 (75,3)

|

60 (68,2)

|

0,45

|

|

Negativo

|

42 (24,1)

|

27 (30,7)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

1 (0,6)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Estado RP

|

|

|

|

|

Positivo

|

108 (62,1)

|

50 (56,8)

|

0,7

|

|

Negativo

|

64 (36,8)

|

37 (42)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

2 (1,1)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Estado Her 2

|

|

|

|

|

Positivo

|

34 (19,5)

|

19 (21,6)

|

0,82

|

|

Negativo

|

138 (79,3)

|

68 (77,3)

|

|

|

Equivoco, no FISH

|

1 (0,6)

|

0

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

1 (0,6)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Ki 67, mediana + desviación estándar

|

36,4 + 22

|

38,7 + 25,3

|

0,70

|

|

Subtipo IHQ

|

|

|

|

|

Luminal A

|

30 (17,2)

|

15 (17)

|

0,16

|

|

Luminal B

|

85 (48,9)

|

31 (35,2)

|

|

|

Triple negativo

|

25 (14,4)

|

20 (22,7)

|

|

|

Luminal-Her 2

|

18 (10,3)

|

13 (14,8)

|

|

|

Her 2 positivo

|

16 (9,2)

|

8 (9,1)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

0

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Número de metástasis

|

|

|

|

|

< 4

|

18 (10,3)

|

32 (36,4)

|

< 0,001

|

|

> 4

|

155 (89,1)

|

54 (61,4)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

1 (0,6)

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

|

Sitio de metástasis

|

|

|

|

|

Ósea

|

123 (70,7)

|

51 (58)

|

0,02

|

|

No

|

51 (29,3)

|

37 (42)

|

|

|

Pulmón

|

59 (33,9)

|

27 (30,7)

|

0,35

|

|

No

|

115 (66,1)

|

61 (69,3)

|

|

|

Hepática

|

39 (22,4)

|

6 (6,8)

|

0,001

|

|

No

|

135 (77,6)

|

82 (93,2)

|

|

|

SNC

|

6 (3,4)

|

2 (2,3 %)

|

0,46

|

|

No

|

168 (96,6)

|

86 (97,7)

|

|

|

Ganglionar a distancia

|

49 (28,2)

|

22 (25)

|

0,34

|

|

No

|

125 (71,8)

|

66 (75)

|

|

|

Pleural

|

19 (10,9)

|

4 (4,5)

|

0,06

|

|

No

|

155 (89,1)

|

84 (95,5)

|

|

|

Otros

|

19 (10,9)

|

3 (13,6)

|

0,02

|

|

No

|

155 (89,1)

|

865 (96,6)

|

|

|

Tamaño del tumor

|

|

|

|

|

T1

|

4 (2,3)

|

2 (2,3)

|

0,02

|

|

T2

|

32 (18,4)

|

14 (15,9)

|

|

|

T3

|

19 (10,9)

|

13 (14,8)

|

|

|

T4a

|

2 (1,1)

|

5 (5,7)

|

|

|

T4b

|

80 (46)

|

34 (38,6)

|

|

|

T4C

|

5 (2,9)

|

3 (3,4)

|

|

|

T4d

|

17 (9,8)

|

17 (19,3)

|

|

|

TX

|

9 (5,2)

|

0

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

6 (3,4)

|

0

|

|

|

Focalidad

|

|

|

|

|

Unifocal

|

157 (90,2)

|

81 (92)

|

0,17

|

|

Multifocal

|

7 (4)

|

3 (3,4)

|

|

|

Multicéntrico

|

3 (1,7)

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

|

Multifocal y multicéntrico

|

0

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

|

Oculto

|

5 (2,9)

|

0

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

2 (1,1)

|

0

|

|

|

N Clínico

|

|

|

|

|

N1

|

58 (33,3)

|

29 (33,3)

|

0,16

|

|

N2

|

58 (33,3)

|

28 (31,8)

|

|

|

N3

|

29 (16,7)

|

24 (27,3)

|

|

|

N0

|

14 (8)

|

6 (6,8)

|

|

|

Nx

|

8 (4,6)

|

0

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

7 (4,1)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

Al evaluar las características del tratamiento se encontraron diferencias significativas

entre los grupos en casi todas sus variables. Así, las pacientes del TC presentaron

significativamente mayor requerimiento de terapia citotóxica, poliquimioterapia y

uso de antracíclicos con taxanos; mientras que las pacientes con TSE recibieron significativamente

más terapia endocrina con inhibidores de aromatasa (IA) y la combinación de IA con

inhibidores de quinasas dependientes de ciclinas (ICDK). La radioterapia se administró

significativamente en mayor proporción en el grupo de TC. No se presentaron diferencias

entre los grupos en lo referente al uso de terapia anti-Her y supresión de la función

ovárica (Tabla 3).

Las características del manejo quirúrgico se presentan en la Tabla 4.

Tabla 3

Características del tratamiento

|

Características

|

Tratamiento sistémico (N = 174)

|

Tratamiento sistémico + quirúrgico (N = 88)

|

P

|

|

Terapia citotóxica

|

|

|

|

|

Monoquimioterapia

|

61 (35,1)

|

20 (22,7)

|

0,002

|

|

Poliquimioterapia

|

70 (40,2)

|

56 (63,6)

|

|

|

No QT/no acepta

|

43 (24,7)

|

12 (13,6)

|

|

|

Medicamentos para quimioterapia

|

|

|

|

|

Taxanos

|

53 (30,5)

|

13 (14,8)

|

0,001

|

|

Antraciclinas

|

14 (8)

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

|

Platinos

|

0

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Capecitabina

|

1 (0,6)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Taxanos y platinos

|

10 (5,7)

|

7 (8)

|

|

|

Taxanos y antraciclinas

|

38 (21,8)

|

40 (45,5)

|

|

|

Taxano y otros

|

6 (3,4)

|

3 (3,4)

|

|

|

Antracíclicos y otros

|

2 (1,1)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

Platinos y otros

|

1 (0,6)

|

0

|

|

|

Taxanos, antraciclinas y platinos

|

3 (1,7)

|

3 (3,4)

|

|

|

Otros

|

3 (1,7)

|

6 (6,8)

|

|

|

No requiere

|

43 (24,7)

|

11 (12,5)

|

|

|

Terapia endocrina

|

|

|

|

|

Tamoxifeno

|

16 (9,2)

|

17 (19,3)

|

0,01

|

|

Inhibidor de aromatasa

|

60 (34,5)

|

26 (29,5)

|

|

|

Fulvestrant

|

4 (2,3)

|

5 (5,7)

|

|

|

Inhibidor de ciclinas y aromatasa

|

37 (21,3)

|

6 (6,8)

|

|

|

Inhibidor de ciclinas y fulvestran

|

2 (1,1)

|

0

|

|

|

Fulvestran anastrazol

|

1 (0,6)

|

0

|

|

|

No recibe

|

11 (6,3)

|

4 (4,5)

|

|

|

No requiere

|

43 (24,7)

|

30 (34,1)

|

|

|

Supresión de la función ovárica

|

|

|

|

|

Quirúrgico

|

19 (10,9)

|

7 (8)

|

0,47

|

|

Medicamento

|

6 (3,4)

|

6 (6,8)

|

|

|

Radioterapia

|

3 (1,7)

|

3 (3,4)

|

|

|

No recibe

|

8 (4,6)

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

|

No requiere

|

138 (79,3)

|

70 (79,5)

|

|

|

Terapia Anti Her 2

|

|

|

|

|

Trastuzumab

|

10 (5,7)

|

10 (11,4)

|

0,4

|

|

Pertuzumab

|

2 (1,1)

|

0

|

|

|

Tratuzumab + pertuzumab

|

25 (14,4)

|

12 (13,6)

|

|

|

No recibe

|

1 (0,6)

|

0

|

|

|

No requiere

|

136 (78,2)

|

66 (75)

|

|

|

Radioterapia locorregional

|

|

|

|

|

Mama

|

7 (4)

|

2 (2,3)

|

< 0,001

|

|

Mama y ganglios locorregionales

|

5 (2,9)

|

6 (6,8)

|

|

|

Reja costal

|

0

|

8 (9,1)

|

|

|

Reja costal y ganglios locorregionales

|

0

|

9 (10,2)

|

|

|

Axila

|

1 (0,6)

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

|

No administran

|

156 (89,7)

|

35 (39,8)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

5 (2,9)

|

27 (30,7)

|

|

|

Radioterapia a la metástasis

|

|

|

|

|

Si

|

70 (40,2)

|

21 (23,9)

|

0,04

|

|

No

|

102 (58,6)

|

67 (76,1)

|

|

|

Desconocido

|

2 (1,2)

|

0

|

|

Tabla 4

Características de manejo quirúrgico

|

Características

|

Tratamiento sistémico + quirúrgico (N = 88)

|

|

Media de N positivos por patología

|

5,3 + 6,2

|

|

Primer manejo

|

|

|

Sistémico

|

78 (88,6)

|

|

Quirúrgico

|

10 (11,4)

|

|

Causa de cirugía

|

|

|

Higiénica

|

24 (27,3)

|

|

Respuesta sistémica pero no local, aunque estable

|

21 (23,9)

|

|

Respuesta clínica completa

|

11 (12,5)

|

|

Sin respuesta sistémica o local

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

Enfermedad sistémica estable y progresión local

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

Otros

|

10 (11,4)

|

|

Desconocido

|

20 (22,7)

|

|

Tipo de cirugía

|

|

|

Mastectomía radical modificada

|

71 (80,7)

|

|

Mastectomía simple

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

Cirugía conservadora y vaciamiento axilar

|

10 (11,4)

|

|

Cirugía conservadora

|

1 (1,1)

|

|

Cirugía conservadora y biopsia de ganglio centinela

|

2 (2,3)

|

|

Vaciamiento axilar

|

2 (2,2)

|

4. Supervivencia

Los 262 pacientes aportaron un total de 6910,92 meses de seguimiento con una media

de 58,38 meses (rango 48,6-68 meses) y una mediana de 36,17 meses (IC 95 % 26,91-45,42).

4.1. Supervivencia libre de progresión

Ocurrieron 114 eventos de progresión, 85 en el grupo de TSE y 29 en el grupo de TC.

La media de SLP en el grupo de TSE fue de 38,56 meses (rango 29,89-47,24); mientras

que para el grupo de TC fue de 72,25 (rango 60,92-83,37); el resultado fue estadísticamente

significativo (p < 0,001) (Figura 1A).

La SLP al año del diagnóstico fue de 79,6 % (IC 95 % 72,2-85,2 %) y 90,2 % (IC 95

% 81,4-95 %); a los cinco años de 11,5 % (IC 95 % 4,6-21,8 %) y 54,6 % (IC 95 % 30,8-67,9

%) para la TSE vs. el TC respectivamente.

4.2. Supervivencia global

Se presentaron 118 muertes, 92 en el grupo de TSE y 26 en el grupo de TC. La mediana

de SG para toda la población fue de 48,63 meses (IC 95 % 40,43-56,82), para el grupo

de TSE fue de 42,4 meses (IC 95 % 33, 23-51,56) y para el grupo de TC fue de 82,33

(IC 95 % 62,1 -102,55), con una diferencia estadísticamente significativa (p < 0,001)

(Figura 1B).

La SG al año del diagnóstico fue de 85,7 % (IC 95 %: 79,4-90,2 %) y 96,4 % (IC 95

%: 89,1-98,8 %); a los cinco años fue de 30 % con IC 95 % 20,8-39,7 % y 59,9 % con

IC 95 % 44,5-72,2 % para el grupo de TSE y para el grupo de TC respectivamente.

Figura 1A

Supervivencia libre de progresión por grupo de tratamiento.

Figura 1B

Supervivencia global discriminada por grupo de tratamiento.

4.3. Ajuste por factores confusores

Con base en los resultados del estudio y lo reportado por la literatura, se consideraron

como variables confusoras para el ajuste la edad, el estado menopaúsico, el tamaño

tumoral, el sitio de metástasis, el número de metástasis, el estado de los receptores

hormonales y de Her 2, el subtipo molecular, el manejo sistémico citotóxico y endocrino.

La SLP muestra un análisis no ajustado con HR 0,34 IC 95 % 0,22-0,52 (p < 0,001) y

la SG de 0,33 IC 95 % 0,21-0,52 (p < 0,001) (Tabla 5).

Tabla 5

Análisis no ajustado de sobrevida libre de progresión y sobrevida global

|

Estimación observada

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sobrevida libre de progresión

|

|

|

Sobrevida global

|

|

|

|

|

HR

|

IC 95 %

|

valor p

|

HR

|

IC 95 %

|

valor p

|

|

Tipo de tratamiento

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sistémico

|

Ref.

|

|

|

Ref

|

|

|

|

Quirúrgico + sistémico

|

0,34

|

0,22-0,52

|

< 0,001

|

0,33

|

0,21 - 0,52

|

< 0,001

|

Los resultados ajustados pueden observarse en la Tabla 6 y muestran que tanto para SLP como para SG hay una asociación que persiste, siendo

estadísticamente significativa a favor de la TC. En las estimaciones ajustadas, la

SLP mostró una asociación significativa con el subtipo triple negativo, la presencia

de metástasis hepática y el tamaño del tumor, siendo de mayor riesgo la clasificación

T4b. Aunque T4a, T4d y Tx mostraron un resultado significativo, el grupo de pacientes

para cada una de estas categorías era pequeño y los intervalos de confianza amplios.

Lo mismo ocurrió con el manejo endocrino y el uso de ICDK con fulvestran. En cuanto

a la estadificación clínica de los ganglios, si bien N1, N2 y N3 tenían la mayor cantidad

de pacientes, los intervalos de confianza para estas categorías también resultaron

amplios.

Tabla 6

Análisis ajustado de sobrevida libre de progresión y sobrevida global

|

|

Estimaciones ajustadas

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sobrevida libre de progresión

|

|

|

|

Sobrevida global

|

|

|

|

|

|

HR

|

IC 95 %

|

|

valor p

|

HR

|

IC 95 %

|

|

valor p

|

|

Tipo de manejo

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sistémico

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Quirúrgico + sistémico

|

0,28

|

0,16 - 0,5

|

|

< 0,001

|

0,23

|

0,13 - 0,43

|

|

< 0,001

|

|

Subtipo molecular

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Her 2

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Luminal A

|

1,3

|

0,2

|

9,4

|

0,814

|

6,8

|

1,0

|

48,3

|

0,056

|

|

Luminal B

|

4,5

|

0,7

|

29,3

|

0,116

|

29,7

|

4,7

|

189,0

|

< 0,001

|

|

Triple negativo

|

3,5

|

1,3

|

9,1

|

0,010

|

13,3

|

4,9

|

36,1

|

< 0,001

|

|

Luminal - Her 2

|

2,6

|

0,4

|

16,6

|

0,313

|

3,9

|

0,6

|

23,6

|

0,138

|

|

Metástasis hepática

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Sí

|

2,2

|

1,2

|

4,0

|

0,009

|

1,6

|

0,9

|

2,7

|

0,078

|

|

Número de metástasis

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

1-3 metástasis

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

> 4 metástasis

|

2,4

|

1,2

|

4,8

|

0,016

|

1,7

|

0,9

|

3,3

|

0,117

|

|

Estadio de cT

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

T1

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

T2

|

5,2

|

1,4

|

19,5

|

0,015

|

6,3

|

1,2

|

33,3

|

0,030

|

|

T3

|

4,3

|

0,9

|

19,3

|

0,059

|

8,9

|

1,6

|

50,8

|

0,014

|

|

T4a

|

9,3

|

1,3

|

67,1

|

0,027

|

62,3

|

8,4

|

461,6

|

< 0,001

|

|

T4b

|

4,7

|

1,2

|

18,2

|

0,023

|

10,8

|

2,1

|

56,7

|

0,005

|

|

T4c

|

34,2

|

5,6

|

207,9

|

< 0,001

|

61,2

|

8,6

|

434,9

|

< 0,001

|

|

T4d

|

4,5

|

1,2

|

17,9

|

0,030

|

10,7

|

2,0

|

57,6

|

0,006

|

|

Tx

|

15,1

|

2,1

|

108,4

|

0,007

|

4,2

|

0,3

|

51,4

|

0,263

|

|

Estadio Cn

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nx

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

N1

|

8,8

|

1,7

|

47,1

|

0,011

|

1,3

|

0,3

|

6,1

|

0,774

|

|

N2

|

14,3

|

2,7

|

76,4

|

0,002

|

2,1

|

0,4

|

10,1

|

0,359

|

|

N3

|

20,1

|

3,5

|

114,0

|

0,001

|

1,8

|

0,3

|

9,1

|

0,487

|

|

N0

|

7,8

|

1,2

|

50,3

|

0,032

|

1,4

|

0,2

|

7,9

|

0,704

|

|

Tipo de quimioterapia

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Poliquimioterapia

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Terapia monoagente

|

1,6

|

1,0

|

2,7

|

0,057

|

1,6

|

1,0

|

2,7

|

0,067

|

|

No recibe

|

1,1

|

0,6

|

2,3

|

0,700

|

1,8

|

0,9

|

3,4

|

0,077

|

|

Terapia endocrina inicial

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

IA+ ICK

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

Ref.

|

|

|

|

|

Tamoxifeno

|

2,5

|

1,0

|

6,6

|

0,060

|

1,3

|

0,5

|

3,7

|

0,622

|

|

IA

|

2,3

|

1,0

|

5,3

|

0,052

|

1,8

|

0,8

|

4,2

|

0,176

|

|

Fulvestran

|

3,5

|

1,0

|

11,9

|

0,042

|

2,7

|

0,8

|

9,2

|

0,111

|

|

ICK +fulvestrant

|

17,8

|

3,2

|

97,9

|

0,001

|

NE

|

|

|

|

|

Fulvestrant + IA

|

NE

|

|

|

|

NE

|

|

|

|

En las estimaciones ajustadas para SG se encontraron asociaciones significativas en

los subtipos luminal B, triple negativo y en la estadificación del tumor. Sin embargo,

al revisar los intervalos de confianza todos eran muy amplios.

Cuando se realiza el análisis de sensibilidad por el propensity score, por las características que difirieron significativamente entre los grupos para

la indicación del tratamiento (T previo, número de metástasis y sitio de la metástasis),

se trazan las curvas de supervivencia libre de progresión (Figura 2A) y global (Figura 2B) ajustadas, en las que se continúa observando la diferencia significativa a favor

del manejo conjunto en cuanto SG y SLP.

Figura 2A

Supervivencia global ajustada

Figura 2B

Supervivencia libre de progresión ajustada

5. Discusión

El cáncer de mama estadio IV es una enfermedad heterogénea e incurable, su manejo

tiene como objetivo la prolongación de la supervivencia y la paliación de los síntomas;

la terapia sistémica es su pilar terapéutico. Sin embargo, se han realizado múltiples

estudios para evaluar si la TC ofrece algún beneficio adicional en los resultados

oncológicos. El presente estudio analizó a tal grupo de pacientes, así como a los

tratados con TSE.

Con una mediana de edad de 56 años y un predominio de pacientes menopaúsicas, este

estudio concuerda con lo reportado en la literatura. A nivel nacional, Díaz et al.

[14] informaron una mediana de edad de 58,8 años y un 62,9 % de posmenopáusicas. Por su

parte, estudios internacionales, en general, reportan una mediana de edad > 50 años

[1,6-9,15-18] y una mayoría de pacientes menopaúsicas [5,7,12,17].

El principal tipo de carcinoma en la cohorte de este estudio fue el ductal infiltrante,

de moderado y alto grado, hormonal positivo, lo que es consistente con la literatura

mundial [6-9,11,14,17-19]. Sin embargo, el subgrupo triple negativo, que es de menor presentación en los diversos

estudios [6,7,12], ocupó el segundo lugar. Tanto en la literatura como en este estudio, los tumores

se clasificaron principalmente en estadio T4 [6,8,11,14,16,20]. Aunque Soran et al. [6] y Thomas et al. [18] informaron en sus ensayos clínicos una mayor frecuencia de tumores pequeños estadio

T2.

La mayoría de las pacientes en este estudio recibieron TSE al igual que lo informado

en gran parte de los estudios retrospectivos [8,11,16-18]; esta indicación se apoya en los resultados de las investigaciones que muestran que

el tratamiento quirúrgico no se asocia a una mayor tasa de SG [1,7,12,19]. Cabe destacar el ensayo clínico E2108 [7] en el que aleatorizaron 256 pacientes a TSE y TC, permitieron el uso de las terapias

sistémicas contemporáneas y evidenciaron la ausencia de efecto en la SG, aunque sí

un mejor control locorregional en el grupo de TC.

Contrario a lo expuesto, esta investigación mostró que sí había mejores resultados

en SG y SLP en las pacientes con TC, incluso después de ajustar por variables confusoras,

lo que es consistente con los hallazgos de varios estudios descriptivos retrospectivos

e incluso un ECA [6,8,11,12,14-19]. Los beneficios en supervivencia de la cirugía locorregional en la paciente en estadio

IV se sustentan en múltiples hipótesis: algunos estudios sugieren que la lesión índice

puede comportarse como reservorio de las células madre enfermas y eliminarlo disminuiría

la probabilidad de desarrollar nuevos sitios de enfermedad a distancia [21]. La resección del tumor primario puede aumentar la angiogénesis sensibilizándolo

a la quimioterapia y facilitando el ingreso del fármaco a las células cancerígenas[22,23]. Extirpar el tejido necrótico y tumoral elimina los tejidos quimioresistentes, restaura

la inmunocompetencia del huésped y reduce el crecimiento de las metástasis [24,25], y resulta en un aumento en la supervivencia de los pacientes [26]. Aunque, por otro lado, existe la hipótesis de que la cirugía en este grupo de pacientes

puede estimular la progresión de la enfermedad por la mayor liberación de factores

de crecimiento locales [27], estos factores de crecimiento a su vez pueden acelerar la proliferación de las células

tumorales circulantes en sangre periférica y afectar la SG y la SLP [24,25,28-30].

En varios estudios [6,8,14,17], incluido este, el estado de los receptores hormonales se informó como un factor

pronóstico independiente, lo que sugiere que la biología del tumor resulta importante